- Ulcers are very common in horses, affecting horses in all disciplines–including pleasure/trail riding horses–with the highest prevalence among racehorses.

- There are two types of equine gastric ulcer syndrome: the more common equine squamous gastric disease (ESGD), which affects the upper region of the stomach; and equine glandular gastric disease (EGGD), which affects the lower region.

- Frequency and intensity of work, environmental stressors and what and when a horse is fed all have an impact on a horse’s risk of ulcers.

Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome

Equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS) is more common in horses than you might think. The majority of horses with gastric ulcers don’t always show symptoms. For those horses that do exhibit clinical signs, here are some to look for:

- Poor performance.

- Poor hair coat and/or body condition.

- Poor appetite or a picky eater.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Abdominal discomfort or colic.

- Behavioral changes (aggressive or nervous).

- Cribbing or other stereotypic vices, like weaving, pawing and stall-walking.

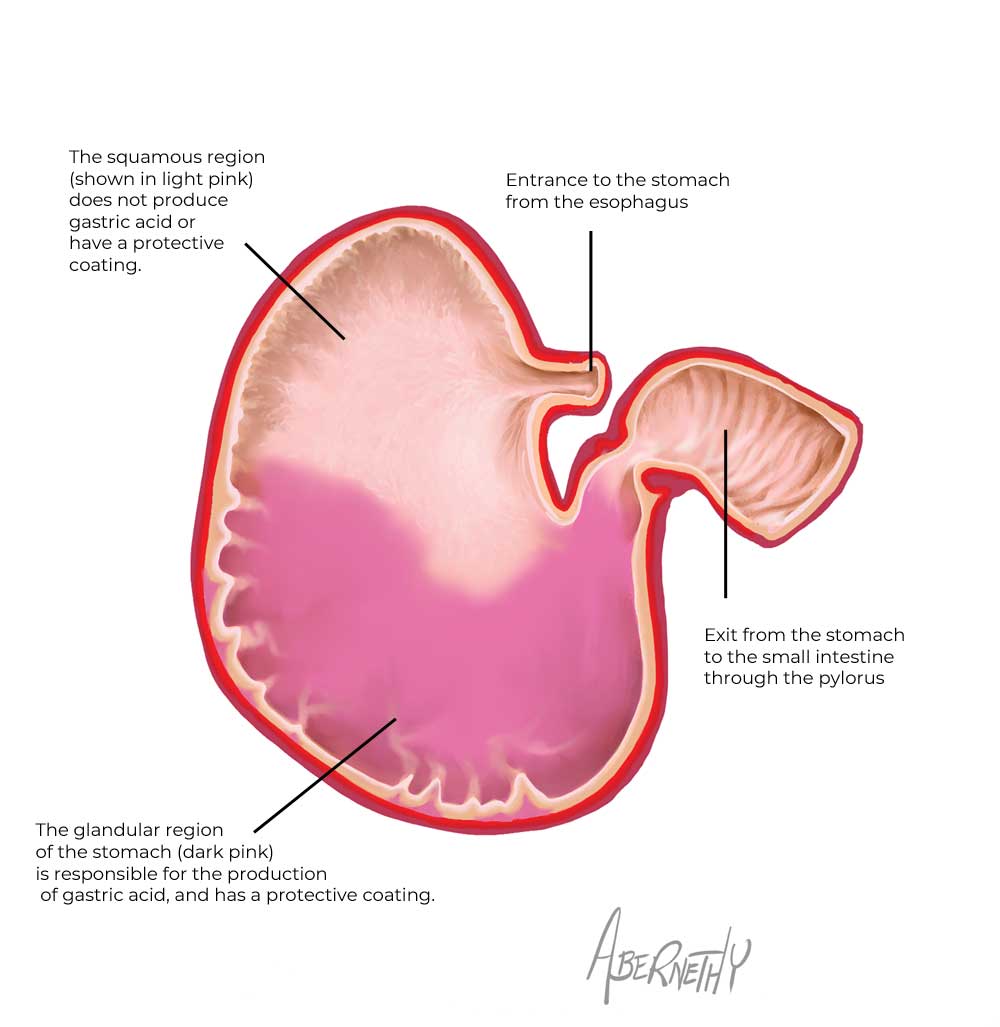

A horse’s stomach has two distinct areas. The lower half is referred to as glandular, where glands produce acid. This portion has a protective lining. The upper half has no glands and no protective lining, and is called the squamous region.

Each has its own form of ulcer disease: the non-glandular portion can get equine squamous gastric disease (ESGD); and the glandular region can have equine glandular gastric disease (EGGD).

Equine Squamous Gastric Disease

The most common form of gastric ulcers, ESGD, is well-known to affect 80 to 100 percent of racehorses, but it’s also prevalent in many other disciplines:

- Show and sport horses: 17-58 percent

- Pleasure horses: 37-59 percent

- Endurance horses: 48 percent when not in competition, rising to 66-93 percent during a competition season.

The greater the intensity of exercise, the greater the likelihood a horse will develop ESGD. At gallop speeds such as racing or other intense activities, the stomach is squeezed between the chest and the abdomen. This pushes stomach acid onto the lining of the upper portion of the stomach that normally isn’t exposed to stomach acid.

Horses ridden mostly at home and not involved in competition may be the least affected, at around 11 percent. However, a variety of management and lifestyle factors increase the incidence.

Equine Glandular Gastric Disease

The glandular portion sits low in the stomach near where food exits into the small intestine. Experts are still defining the prevalence of EGGD, since it was just recently recognized through the use of longer endoscopes that are able to reach to the very bottom of the stomach. Reports estimate approximately 57 percent of horses are affected with EGGD. Unexplained weight loss is a common complaint.

Interestingly, EGGD is seen in horses that are managed well with good lifestyles and low starch/high forage diets. The glandular lining of the stomach normally is bathed in a very acidic pH, so dietary measures don’t play a significant role in managing EGGD.

Read more about nutrition and ulcer management here.

Normal defense mechanisms protect the glandular lining from excess acid exposure. Breakdown of these defenses may contribute to development of EGGD, such as can result from high or long-term doses of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like phenylbutazone, ketoprofen, flunixin meglumine, and firocoxib (Equioxx).

Another important element in the development of EGGD relates to the number of days a horse is exercised per week. A horse ridden six to seven days a week is three and a half times more likely to have EGGD compared to a horse ridden five or fewer days per week. At least two rest days per week are important in minimizing the risk of EGGD.

Interestingly, EGGD is seen in horses that are managed well with good lifestyles and low starch/high forage diets. The glandular lining of the stomach normally is bathed in a very acidic pH, so dietary measures don’t play a significant role in managing EGGD.

Other factors associated with EGGD include situations that add to behavioral stress, such as the number of riders and/or handlers a horse experiences, or isolation of a horse from the herd and social interaction. For example, horses stabled apart from direct contact with others show a high incidence of EGGD.

It isn’t always possible to identify when a horse is stressed. It’s not unusual for an anxious and nervous horse with stall vices to be ulcer-free, while a seemingly calm horse that stands quietly in his stall has stomach ulcers.

Prevention and Treatment of Ulcers

Prevention of ESGD relies to some degree on dietary measures (see Nutritional Management for Equine Ulcer Prevention) along with lifestyle adjustments that minimize a horse’s stress. The more owners do with their horses, the greater the horse’s chance of developing gastric ulcers, especially with transport and changes in routine while away from home. Some horses adapt well to changing routines, active training, competition, and being around strange horses, while others do not.

Treatment of ESGD is based on the principle of “no acid, no ulcer.” Acid suppression is achieved with medication, namely omeprazole (GastroGard). The goal is to raise the pH of the stomach for at least 16 hours in a 24-hour period.

Timing of feeding significantly impacts effectiveness of oral omeprazole treatment. The amount that enters the bloodstream to exert an active effect may decrease by as much as 66 percent when a horse has access to free choice hay.

A better strategy is to fast the horse overnight and then administer omeprazole 60 to 90 minutes prior to the morning feeding. This achieves a greater amount and duration of acid suppression than horses fed free-choice hay day and night.

Even with this strategy, once-a-day treatment with oral omeprazole doesn’t maintain acid suppression for a full 24 hours, or even the desired 16 or more hours. As it turns out, stomach pH is raised for only a four to six hour period. This is especially true when the horse has access to free-choice hay, which stimulates stomach acid secretion whenever he eats. Still, omeprazole is the drug of choice to use for EGUS treatment and it does help.

Currently an intramuscular (IM) formulation of omeprazole is in development, although it’s not yet available in the U.S. The IM form of omeprazole gives results within 24 hours. It is injected weekly to suppress acid, increasing pH for 80 percent of the time between doses. Longer durations of acid suppression translate to better healing.

This article originally appeared in the May 2019 issue of Horse Illustrated magazine. Click here to subscribe!

A question for the author:

Does long term use of compromise bone in horses as it can in humans?