Thanks to recent equine neuroscience research, we’re gaining true understanding of the connection between equine brain function and effective training. These takeaways from a recent groundbreaking seminar debunk a few myths and can help us work better with our horse’s true nature by better understanding their brains.

Neuroscience Meeting Training

Stephen Peters, PsyD, a lifelong horseman and human neuropsychologist who specializes in brain function and memory, co-authored Evidence-Based Horsemanship with Martin Black, a clinician who has worked with thousands of horses. Their book connects equine brain function research with horsemanship methods that mesh with the horse’s brain makeup.

“Over the years, I started to explore neurologically based horsemanship from my work in human memory and brain health,” says Peters.

Mark Rashid, author of Finding the Missed Path: The Art of Restarting Horses, teaches clinics worldwide based on training from the horse’s point of view.

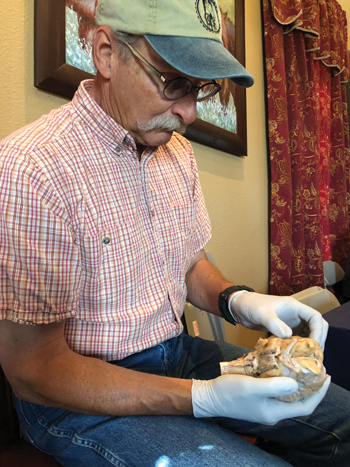

Jim Masterson is the founder of the Masterson Method of equine bodywork that involves the horse’s input as a vital factor of the healing process.

Their goal was to explain why horses do what they do from a neurological standpoint and to use this to work with horses in ways that align with the true nature of the horse rather than against it.

Basic Design

The human brain weighs about 3 pounds, or 1/50th of our total body mass, whereas an average adult horse brain weighs about 2.5 pounds—1/500th of their total body mass. This debunks the myth of the “walnut-sized” horse brain.

A key difference in the human brain versus the equine brain is the size of the frontal lobe, which is what allows abstract thinking, planning, strategy and forecasting of future events in humans. In the horse, the frontal lobe is very small compared to humans. In horses, this area is used for voluntary movement, like when a horse chooses to walk next to us, and not abstract thinking.

“In fundamental ways, our brains are hardwired very differently,” says Rashid. “We humans are hardwired to think and plan, then take action. Horses, on the other hand, are hardwired to move in response to stimuli. When we understand and work with this reality, our training takes a whole new approach.”

Abstract Thought

Seminar attendee Crissi McDonald, also an equine professional who teaches horsemanship internationally, describes how she applied the knowledge of brain differences to her understanding of horse/human interactions.

“It’s not that horses don’t think like we do,” she says. “It’s that they can’t think like we do. Without a well-developed frontal lobe, horses cannot hold grudges, plot revenge, try to win, plan a way to get out of working or take pleasure in making us mad—even though these are ideas that generations of horsemen have believed, especially during a frustrating experience with a horse.”

Peters agrees, adding that horses simply cannot have abstract thoughts like respect and disrespect or take action based on intentional outcomes of winning or beating the system. “Instead, I believe that actions we label as misbehavior actually stem from the question they ask us all the time: ‘Am I safe?’” he says.

Am I Safe?

Margaret Zancanella, a pleasure rider and seminar attendee, shares her new understanding of this concept.

“We learned the cause and effect of different brain chemicals and how we can help our horse release the beneficial brain chemicals that will help them relax and learn,” she says. “When a horse doesn’t understand or can’t recognize something, he perceives everything as a predatory threat, and the stress puts them in the sympathetic nervous system: the fight, flight or freeze zone.”

Horses show they’re in the sympathetic nervous system in a few ways: their head raises above their withers, they show some white around their eyes, their body is tight and braced, they’re worried and whinnying, or they’re jittery and can’t stand still.

“When our horse is worried, he’s asking us, ‘Am I safe?’” says Zancanella. “When we recognize this, we can answer, ‘Yes, you’re safe,’ by being the calm in the storm and staying present and grounded. This helps them downshift to their parasympathetic nervous system—the rest, digest and relax zone.”

Release, Relief, and Soak

Many horse people know to release pressure to give a reward when the horse is doing what he is asked.

“The release starts the teaching,” says McDonald. “But it’s the relief—from pausing a few seconds before asking again and allowing a day or two of ‘soak time’ to assimilate the new skill—that allows the learning to take place.”

This relief triggers the chemical release of dopamine and allows for dendrite growth—the sign that the brain is growing and learning. On the opposite end of the spectrum, constant stress and pressure can actually decrease brain size and short-circuit learning.

“We can grow our horse’s brain, or we can dumb it down by how we handle them and train them,” says Peters.

“In training, that pause or dwell time is vital to the horse assimilating information,” he adds. “Pause long enough so you see lots of licking and chewing. Let the horse lower his head and graze if you can. Once he starts to self-regulate and shift down to parasympathetic mode, everything comes more easily.”

McDonald realized the wisdom of slowing down—breathing, cues, teaching speed and quickness of a lesson—when working on a new movement with her horse. Now, she allows him to process instead of rushing from point A to point B.

“Help your horse stay in parasympathetic mode by helping him look for the answer and stay curious,” says Rashid. “If he’s worried, he’ll go to sympathetic mode where he can’t learn. Use just enough pressure and incentive to help him look for the answer, but not so much pressure he has to find a way out to protect himself.”

The Path Ahead

“Since the clinic, I recognize when my horses are feeling stressed,” says Zancanella. “I use the techniques Peters shared that help me be the calm in the storm, like not clamping down on the lead rope and trying to restrain my horse when he’s worried.”

Instead, Zancanella relaxes herself, tells her horse that he is safe and ensures they both switch to using their parasympathetic nervous system. Even talented horsemen like Rashid came away from the seminar with new ideas and insights into how to better work with horses.

“Over many years, I’ve discovered ways of working with the horse and not against his nature,” he says. “Understanding how a horse’s brain works and how they truly process information can, I believe, help steer the course of future horsemanship for the better.”

This article on your horse’s brain appeared in the February 2020 issue of Horse Illustrated magazine. Click here to subscribe!

[…] important to remember that horses do not have the same brain development as we do. Without the level of development in the frontal lobe that we have, the horse […]