Saddle fitting can be intimidating, but understanding the basics allows you to choose a saddle that best fits you and your horse. Not only is a good-fitting saddle more enjoyable to ride in, but ill-fitting saddles can also cause long-term damage to your horse’s shoulders and back. Pain from a poorly fitted saddle can cause behavioral issues and even career-ending lameness.

“Horses do not consciously behave poorly,” Schleese says. “The horse can react very fast to a very small amount of pressure when it’s in the wrong spot.”

Thankfully, advances in technology have greatly benefitted the saddle-fitting industry. Cameras, infrared heat mapping and equine treadmills equip saddle fitters to understand horses’ saddle fit needs better than ever.

Signs of Damage

Recognizing the signs of an ill-fitting saddle is the first step toward making a change. According to Schleese, the pressure it takes to crush a grape between your fingers is enough to irritate a horse.

Ill-fitting saddles can pinch nerves, cause muscle atrophy, and make horses numb as they work. Think of pinching your skin with your fingernails: after a while, the pain and irritation is dulled, but the injury is there.

An ill-fitting saddle can first cause wither blisters, which are raised bumps on or near the withers during riding. Dry spots (within the saddle sweat stain) on the back and withers after exercise, as well as white hair growth, indicate something is wrong. Both of these signs occur when intense pressure is applied to the skin. They are precursors to cartilage degradation in the shoulders, withers and back—an unfixable problem.

Aside from the comfort and happiness of the horse, a well-fitting saddle reduces stress.

“When a horse is experiencing [pain], the heart rate goes up, releasing [the stress hormone] cortisol in the blood,” says Schleese. “[Cortisol] means high risk of colic and ulcers.”

While there are several factors that go into fitting a saddle to a horse, Schleese says that understanding three main points of fitting will set horse owners on the right path.

1. Withers and Gullet Width

Riders learn that a saddle should never touch the top of the withers, but don’t realize the sides of the withers are also incredibly sensitive.

“The top is just bone and cartilage, but the sides have all these nerves,” Schleese says. “In nature, this is where stallions bite each other. If a horse is bitten there, he will stop moving forward. It ignites the nerves.”

Horses with saddles that pinch their withers show reluctance to move forward and they hollow their backs, making it impossible to perform in a safe and athletic manner. More stress is put on the tendons in their legs as they move awkwardly, trying to relieve the pinching sensation the saddle applies to the withers.

Use a pencil to determine if the saddle is wide enough for the horse’s shoulders. Test this with the saddle resting on the horse with no saddle pad. Take a pencil and slide it under the sides of the saddle; the pencil should slide easily and evenly with continuous contact between horse and saddle.

The withers need 4 inches of clearance on top and 2 to 3 inches around the sides to keep from compromising the muscles and nerves in the area. Saddles that are too narrow will pinch this area, while saddles that are too wide will fall downward and “crush” the withers and the shoulders.

Think of wearing a shoe that is too big or small. If the shoe is too small, your toes are cramped. Too big, and your toes slam into the front of the shoe while running because there is nothing holding your foot in the correct position.

2. Weight Distribution and Saddle Length

Balance is one of the most important factors in saddle fitting. Having a saddle that fits well at the withers with even contact down the back is vital. Saddle bars are meant to support your weight and distribute it over your horse’s back muscles, but a horse that is under-muscled or overly fat might experience the bars pressing harder in some places, causing stress.

According to Schleese, an English saddle’s bars begin at the front D-ring and extend all the way down the saddle. On a western saddle, which is designed to have things attach to it for trail rides and ranching needs, the weight-supporting bars begin at the first concho and end where the seat connects to the skirt.

The bars should sit between the end of the mane, where the shoulder blade often ends, and the “ring of light,” which is where the hair glows in a curved line on the back. The ring of light signifies a transition from the horse’s full ribs to his lumbar (lower back) vertebrae, which have flat transverse processes that are not connected to the sternum with a rib, and should not bear weight.

To check a saddle’s length, Schleese marks a horse with chalk where the mane ends and the ring of light begins, puts the saddle on without a pad, and sees where the bars of the saddle end in correlation to the chalk marks. The bars should be within the marks.

3. Bar Angles

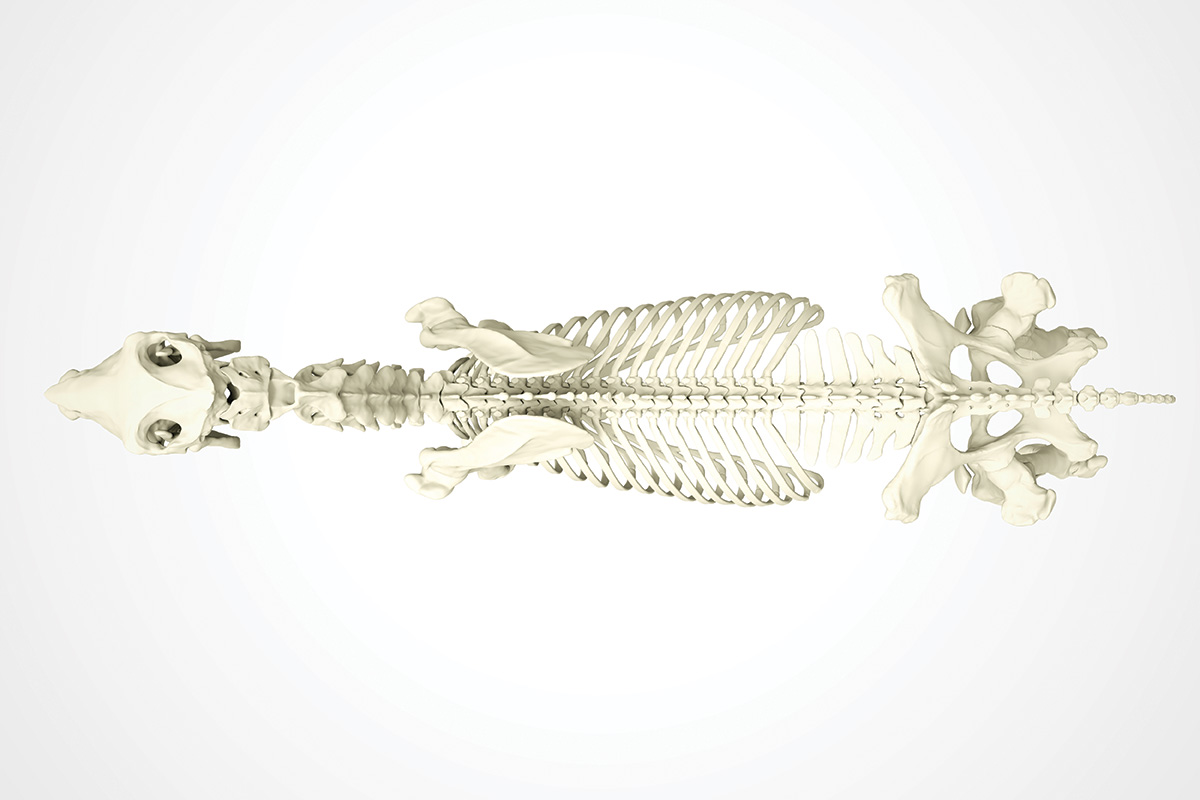

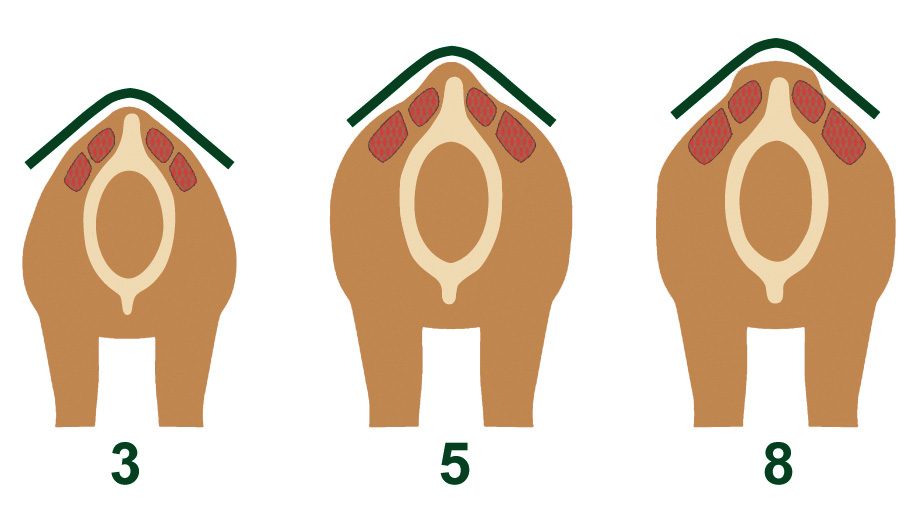

As horses age, they change shape. Starting with round barrels, horses become more angled as they work and build muscle. This is because their rib cages are suspended by muscles instead of a skeletal structure. Their posture changes as they grow and learn to use their bodies to support weight and carry themselves well. Their shoulder blades move upwards and back as they build muscles.

When fitting a horse, consider age and level of work. A young horse will likely need flatter bars, while a well-trained older horse will need a saddle with steeper bars.

Saddle Fitting to the Rider

Fitting a saddle can often take a horse-focused turn, but remember that you are an important part of the equation for a more thoughtful saddle-fitting process.

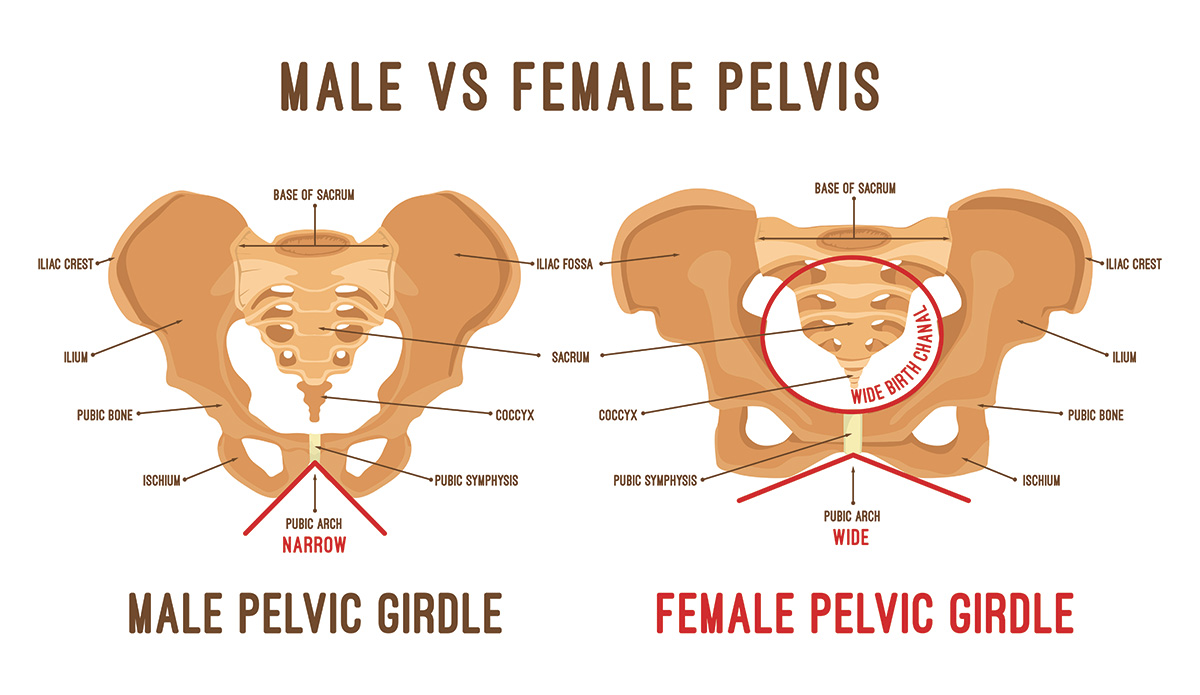

The anatomical differences between a man and woman make for some surprising saddle seat variations. Sitting in a gender-inappropriate saddle is uncomfortable, and if you’re protecting yourself from discomfort, you will experience tension and a jerky rhythm will translate down to the horse and affect his performance.

Men have straighter lower backs, longer tailbones, and lower buttocks. This means they need a flatter saddle seat that will allow them to keep their heels under themselves while riding.

In contrast, women have more lower back curvature, a shorter tailbone, and higher buttocks. The higher buttock muscles mean that in a flat saddle seat, a woman’s pelvis will rotate backwards, giving the appearance of a rounded back. A saddle made for a woman will have more rise in the back of the seat, giving the buttocks a comfortable boost and allowing the spine to remain in its natural position.

Jochen Schleese’s Motivation

Jochen Schleese has been working to build better saddles for both horse and rider since 1982. His passion stems from a personal experience with his Hanoverian gelding, Pirat. A three-day eventer, Schleese and Pirat qualified for the 1984 European Championships. Unfortunately, due to lameness in the left shoulder, Pirat and Schleese dropped out of the competition.

“He started to have a little bit of an irregular step,” says Schleese. “And when you compete for your country, you’re under a microscope. Disqualification happens because [the horse] is not 100 percent sound.”

The team veterinarians tried everything to help Pirat stay comfortable, but he was eventually retired. Looking back, Schleese is certain that the saddle caused Pirat’s pain, and his experience helped him start a new chapter in his saddle-making career.

Through his educational company Saddlefit 4 Life, Schleese teaches hundreds of people every year about saddle fit and certifies equine ergonomists, independent experts who use precise measurements and science to analyze the fit of a saddle to horse and rider. The Schleese team has helped over 200,000 horses worldwide over the years, and they believe that education is key to making the necessary changes in the industry.

Hear more of Schleese’s insight on saddle fitting in this episode of Barn Banter.

Saddle fit is unique, and one size never fits all. With basic knowledge, it’s easier to pick out a saddle that fits your horse and eliminates unnecessary pain.

This article about saddle fitting appeared in the April 2022 issue of Horse Illustrated magazine. Click here to subscribe!