Even in the 21st century, some people still make a living “cowboying” — or working as freelance cowboys.

These freelance cowboys load up their horses and dogs, drive where needed and get the work done, from gathering, sorting and shipping to doctoring, vaccinating, branding, castrating and weaning. It all revolves around cattle, but tasks vary depending on the time of year.

The demand for skilled day workers is such that experienced individuals can make this a full-time job. We caught up with three of them for a glimpse at their lives.

Gen Z Cowgirl

Like most Gen Z-ers, Makenzie Higgs, 21, is totally tech-savvy, although she doesn’t live a bright-lights, big-city lifestyle.

She’s grown up on her family’s ranch in Cedar Point, Kansas, where they raise Angus cattle and registered Quarter Horses. Her job is training horses and day-working. She’s been riding with her dad since she was 1 year old, and got her first horse at age 5.

“My dad and my older brother, Troy, are both mentors to me,” says Higgs, who has been day-working for pay since age 16. “They completely make a living with cattle and horses. My mom is a schoolteacher.”

“I missed track and softball season because of school closure, so I was able to day work more,” she adds. “That really sealed it for me.” Higgs graduated high school in the “Covid year” of 2020.

Higgs attended Butler Community College in El Dorado, Kansas, and graduated in May 2022 with her associate’s degree in Farm and Ranch Management.

“I took some college classes in high school my senior year and was still able to day work during college,” she says.

Whether she’s working or rodeoing, her best horse is Lippy, an 12-year-old sorrel Quarter Horse gelding. Her other mount is Indy, a 5-year-old Quarter Horse gelding. Because she always has one or two horses she’s taken in for training, they also get used for day work.

She usually brings along her two cattle dogs, Dez and Daya.

Higgs consistently day works with a group of four to six people, including her dad, brother, and boyfriend, Brenden Jantz.

“When you work with people so much, you can read each other’s minds,” she says. “We all work well together, and the job goes smoother.”

The day’s tasks vary according to season. For example, early fall work includes branding, vaccinating, castrating and deworming calves, then weaning and preg-checking cows.

Higgs learned to rope at a young age from her dad and brother, which comes in handy when doing her favorite chore: doctoring cattle.

“We head and heel them and lay them down in the pasture to doctor them,” she explains. “But if you have to rope more than 20, it’s a lot of work and you and the horses get tired. If we have a lot to doctor, then we’ll bring the whole group up to the pens and sort out the ones that need doctoring.”

Her roping skills aren’t just used for work. Higgs, who both heads and heels, loves competing and rodeos regularly.

“I’ve always really enjoyed roping, just the whole atmosphere,” she says.

As for the future, although she would be happy to continue day working in her area, she’s open to doing seasonal day work in another part of the country.

“I’d love to keep doing this, but I wouldn’t mind moving to manage a ranch.”

Freelance Cowboy in the Sunshine State

Fourth generation Florida cattleman Myron Albritton, 52, has been a freelance day-working cowboy since he was 15 years old.

Raised on a 1,000-acre family-owned commercial cattle ranch in the heart of the Sunshine State’s beef county, Albritton’s father, grandfather and great-grandfather all did day work. As a kid, he toyed with the idea of being a fireman, but says, “I stayed with the cowboy stuff.”

Albritton, who is married with three children, runs 500 to 600 head of his own commercial cows, mostly Braford and Brangus because the Brahman bloodlines can handle Florida heat and bugs.

He’s become a lead day worker in his area, so ranchers call Albritton and tell him what they need. He creates a schedule and coordinates a crew of day workers, including his 26-year-old son, Blaine.

“You build up a name over time, then it becomes a steady job—you can work seven days a week if you want to,” says Albritton, who typically day works for at least 100 different operations in a year, mostly within a 60-mile radius of his place in Venus.

In 1987, when he started day working, pay was $65 per day. Average pay in south Florida for a good worker today is $200 per day.

Depending on the season and what needs to be done, Albritton may spend a month working at one operation, or day work at different places every day.

He maintains a string of two to four horses that are registered Quarter Horses or grade. It’s common for many day workers to ride young horses and then sell them.

“Riding them every day, you develop a well-mannered, well-broke horse,” he says. “Wet saddle blankets are what get them broke.”

Albritton’s go-to horse is Fred, an 8-year-old grade gelding he says he’ll probably never sell.

When Albritton loads his horse for the day in his stock trailer, he always takes along two or three dogs, depending on the day’s chores. He uses Florida Cur dogs and finds them invaluable.

“Once the cows are ‘dog broke’ [used to dogs and respect them], they’ll walk to the pens nice and easy,” he says. “We’re typically working 200 head of cattle in a group and four dogs can handle that pretty easily.

If there are stragglers hiding in the palmettos and brush, you can send the dogs and they’ll bring them up. It simplifies things, keeps the cows from running, and saves a lot of riding.”

During the hottest months, he is mounted up and working by the time the sun rises to beat the heat. He aims to finish by lunch, if not before.

“When I go to work, I don’t consider it work because I love cows,” says Albritton. “My wife is a schoolteacher, and she envies me.”

Working the Flint Hills

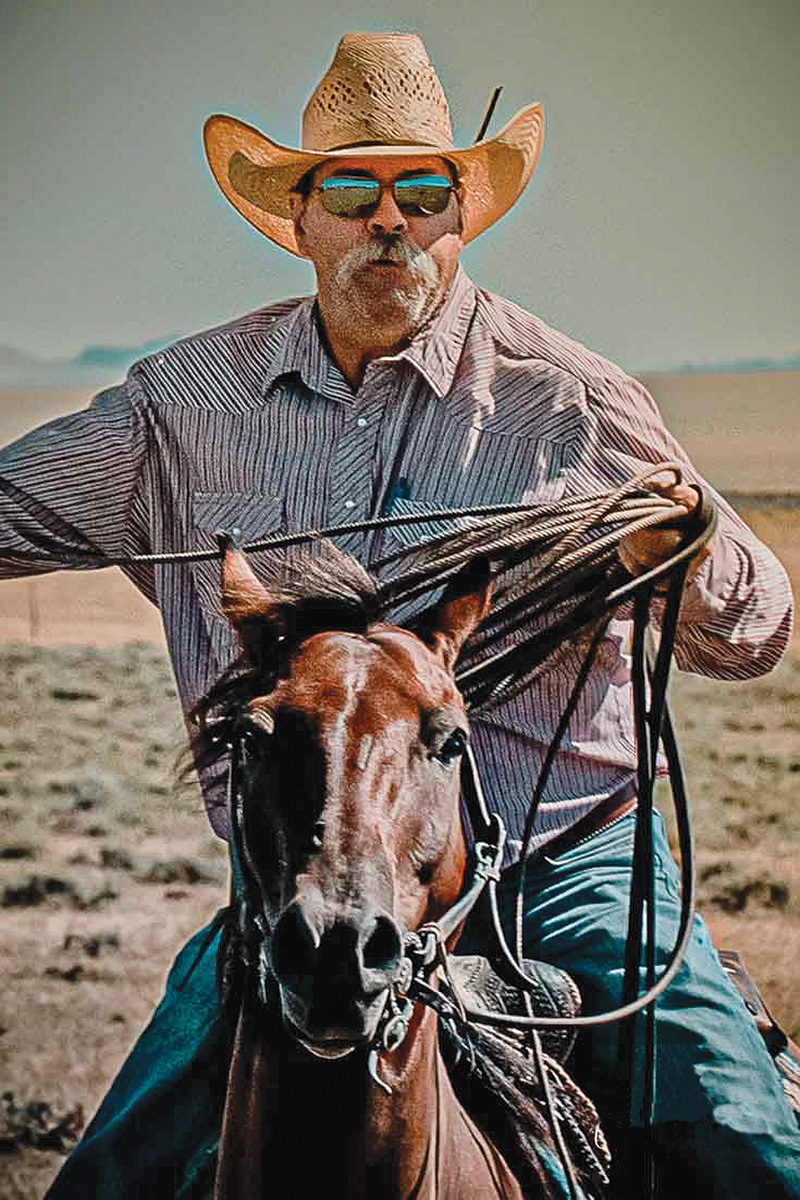

Raised with cattle and horses, Ed McClintock of Soldier, Kansas, grew up in Jackson County.

McClintock, 59, was a farrier for 19 years. When painful knees began to make that career difficult, he still wanted to work with livestock.

“A friend offered me a job taking care of his feedlot and it went from there,” he says. “When I quit shoeing horses, my knees quit bothering me.”

Throughout the years he was a farrier, McClintock also day worked on ranches. He has his own place where he runs about 60 head of commercial cattle. His grown son, Tyrel, helps with their cattle operation and day working.

McClintock day works full time for six different operations in about a 40-mile radius of his ranch and stays busy seven days a week.

His four-legged work partners include several horses and trusty dogs.

McClintock typically owns four to six horses, usually 3- and 4-year-olds, which he sells once they’re well broke.

His oldest horse is Little Steve (named after the friend he bought him from). Although only 14.2 hands, the 9-year-old registered Quarter Horse gelding is stout and reliable.

“I really like him and probably won’t sell him,” says McClintock. “I’ve doctored a lot of cattle and ranch rodeoed on him. I’ve roped 1,800-pound bulls and 1,200-pound cows on him.” His working dogs include a Border Collie, a Border Collie/Australian Kelpie cross, and an Australian Kelpie.

He uses the dogs to gather cattle and to drive ornery cows out of the brush. He can also tell a dog to sit in a gate opening to keep cattle from going through.

McClintock takes pride in being able to “read” cattle and work them with little stress.

While many people use 35- to 40-foot ropes, he carries a 60-foot rope. That extra length buys a little more time, which is helpful when riding young horses.

If a cow requires doctoring but isn’t close to the pens and chute, McClintock has mastered a way to do this horseback. After roping a cow, he’ll circle her. This pulls the rope around her legs and pulls her head back to her flank.

“You can ease them down to the ground, tie their legs and doctor them,” he explains. “It’s easier on the cattle; you’re not tripping or jerking them, and you can lay them down really nice this way.”

In his area, day-working freelance cowboys get paid by the hour when working at feedlots, and by the day at ranches.

“I live the perfect life, taking care of cattle and making sure they’re healthy.”

The Florida Beef IndustryDomesticated cattle were introduced to Florida centuries ago by Spanish explorers. What Ponce De León set in motion in 1521 with a few head eventually grew into a thriving economy. According to Florida Cattle Ranchers, the beef cattle herd in Florida is currently valued at over $1 billion. It’s known as a cow-calf state, meaning the calves are born and raised in Florida, but shipped to feedlots in other states for “finishing” and then processed into beef. The state’s cattle crop exceeds 800,000 calves annually. |

This article about freelance cowboys appeared in the January/February 2023 issue of Horse Illustrated magazine. Click here to subscribe!