Marked by fluid lead changes around a cone-marked course, western riding is a challenging class for all-around competitors. But with skill, preparation and careful navigation, you can guide your horse to a penalty-free score. Here, trainer Bruce Vickery shares his advice to confidently tackle the western riding class.

The Goal

“Scoring is based on quality of movement, the quality of the change, smooth transitions, timing, the placement of your transitions and the placement of your lead changes,” says Vickery. “You want to do everything you can to stay out of the penalty zone.”

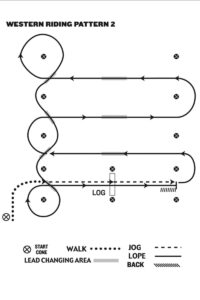

Penalties occur mainly when you fail to change leads within the designated change box written on the pattern. Whether it’s changing leads too early or too late, each stride outside the invisible box incurs point penalties.

The Pattern Unpacked

Western riding patterns are posted at the show and are also printed in association rule books. For example, the American Quarter Horse Association (AQHA) has nine regular patterns. Each AQHA pattern starts out with a walk-in. Vickery suggests establishing a nice, cadenced walk without checking your horse’s stride as you approach your first cone.

“Once you’re at the cone and the judge nods to you to start the pattern, you’ll want to walk with your hand down and let your horse walk in a cadenced fashion,” he says. “The next transition for each of the patterns is going to be the jog. It’s really important to plan where you begin your jog.”

You’ll be jogging over a single pole on the ground as one of your maneuvers. Vickery says to make sure you approach the log straight on, with cadence.

“You want to practice so that the rhythm and speed remain the same before, over and after the pole,” says Vickery. “You don’t want to start out slow, jog over the pole, and then be moving faster.”

Depending on the pattern, you’ll ask your horse for a lope, and you’ll either start coming around to go down the line of cones, or you’ll go across the center of the arena for those lead changes.

If you’re going down the line first, Vickery says you’ll want to avoid making the corner on to the line too wide, which can throw off your sequence of lead changes down the line.

“You almost want to square the corner off so you can be straight heading down the line,” he says. “You’ll begin counting strides toward your first lead change after the first cone.”

Also read – How to Tack Up for Western Riding

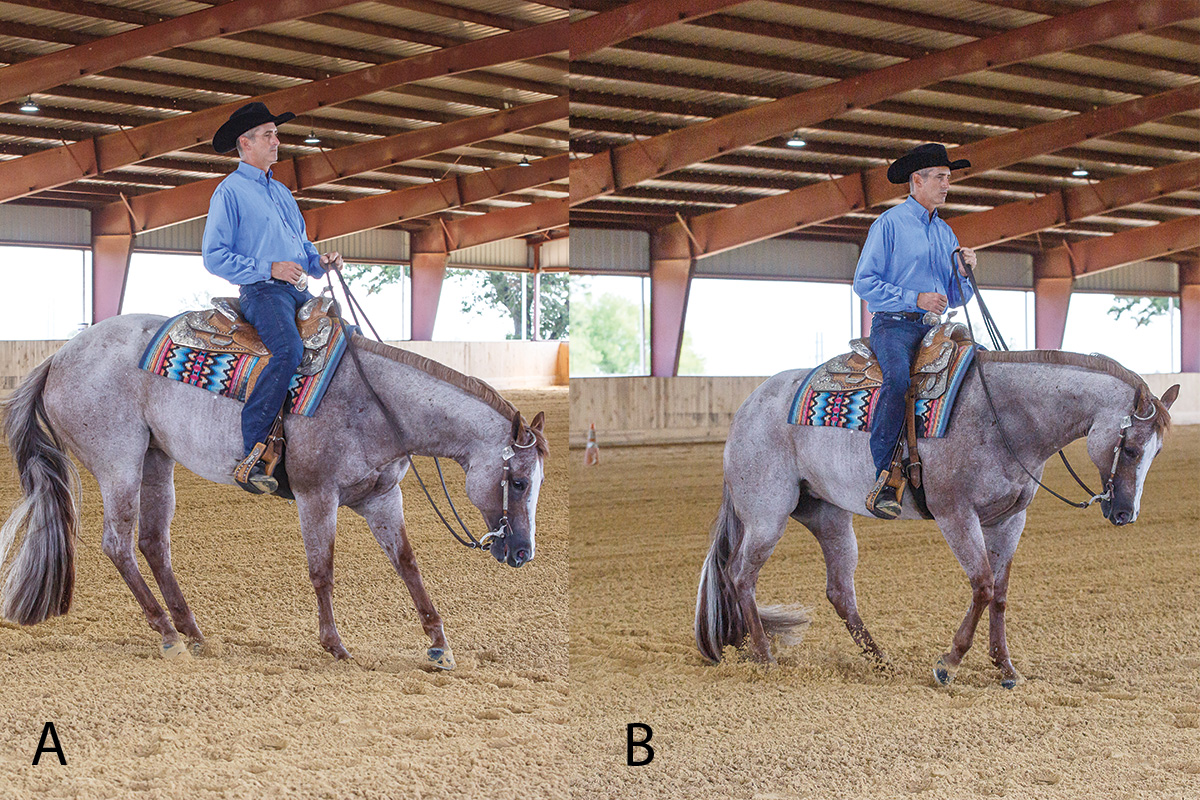

After each change, Vickery suggests not dwelling on the lead change until it’s time for your next one—this reduces your involuntary anticipation of the change, which can trigger your horse’s anticipation.

After changing leads several times, some patterns will have you loping across the arena and changing in the center before turning to the left or right around the cones at the opposite side of the arena.

All patterns will include a lope-over log—the same log you jogged over earlier in the pattern. You’ll either cross it as you are going back and forth across the arena, or at the end of that series of changes. Either way, Vickery suggests counting your strides to the pole to make sure you hit it after your horse has touched down his last front leg and gathered himself up to reach out with his back legs.

“Remember, you want to maintain the same rhythm up to the pole and afterward without changing,” he says.

Your pattern will include a stop and backup. Your horse should stop on his hind end with his head level, not thrown into the air. You will then ask him to back with cadence.

“Your backup doesn’t have to be fast, but it needs to show your horse is willing to do it,” Vickery says.

At the conclusion of the pattern, you will exit the arena.

Challenges

Because the western riding pattern and course contains so many elements—all three gaits, jog and lope-over poles, and between seven and eight lead changes—Vickery says timing can be a challenge.

“Many riders struggle with figuring out where they need to execute the [lead] changes,” he says. “More times than not, I think people anticipate those changes, and that transmits to the horse, causing him to want to change.”

To combat anticipation, Vickery reminds you to stay patient, quiet and wait until you’re in position to start thinking about your change. Going down the line, where you’re serpentining between cones that are 30 to 50 feet apart, Vickery advises counting your strides. But first, it’s a good idea to find out how far apart they are on the day of the show. You can ask show management or a trainer at the show.

“As you approach the point between two cones, start counting [strides]: ‘1, 2, 3, change,’” Vickery says. “If you’ve got a long line, like 50 feet in between each cone, it’s probably going to be a little bit more—maybe ‘1, 2, 3, 4, change.’”

On the path across the arena, you’ll change leads in the middle between the cones. To see the approximate spot in which you should make your lead change, you’ll need to gauge the middle of the arena. For many of the patterns, you’ll see the pole lined up in the middle, which aligns with where you need to change. If not, pick a marker on the arena wall to line up with. Vickery suggests preparing for your change only a couple of strides before that point to avoid anticipation, rather than thinking about it from the time you turn to go across the arena.

Before entering your first western riding class, Vickery advises practicing the entire pattern a few times at home.

“For a novice, it’s a good idea to practice the whole pattern a little bit, just so that you get your feet wet, you get a feel for the spacing and where you need to go,” he says. “But after you’ve done it a few times, you want to do bits and pieces, otherwise your horse will be thinking exactly where to go all the time.”

Focusing on one part of the pattern at a time will help increase your skill level without your horse anticipating the pattern.

This article about acing your western riding pattern appeared in the November/December 2021 issue of Horse Illustrated magazine. Click here to subscribe!