What do you picture when you think of a horse pasture? Probably a beautiful, rolling carpet of even, green grass. In reality, they are too often a piece of hard, compacted ground laced with tall weeds going to seed, spreading more weeds. Little, if any, productive grasses exist between bare spots that become dust bowls in the summer and mud holes in the winter. That’s why proper horse pasture management is key.

Vigorous grasslands are also an important component of a healthy, dynamic ecosystem; pastures contribute to creating healthy soils, which in turn provide habitat for microorganisms, beetles and many other beneficial insects, and larger wildlife.

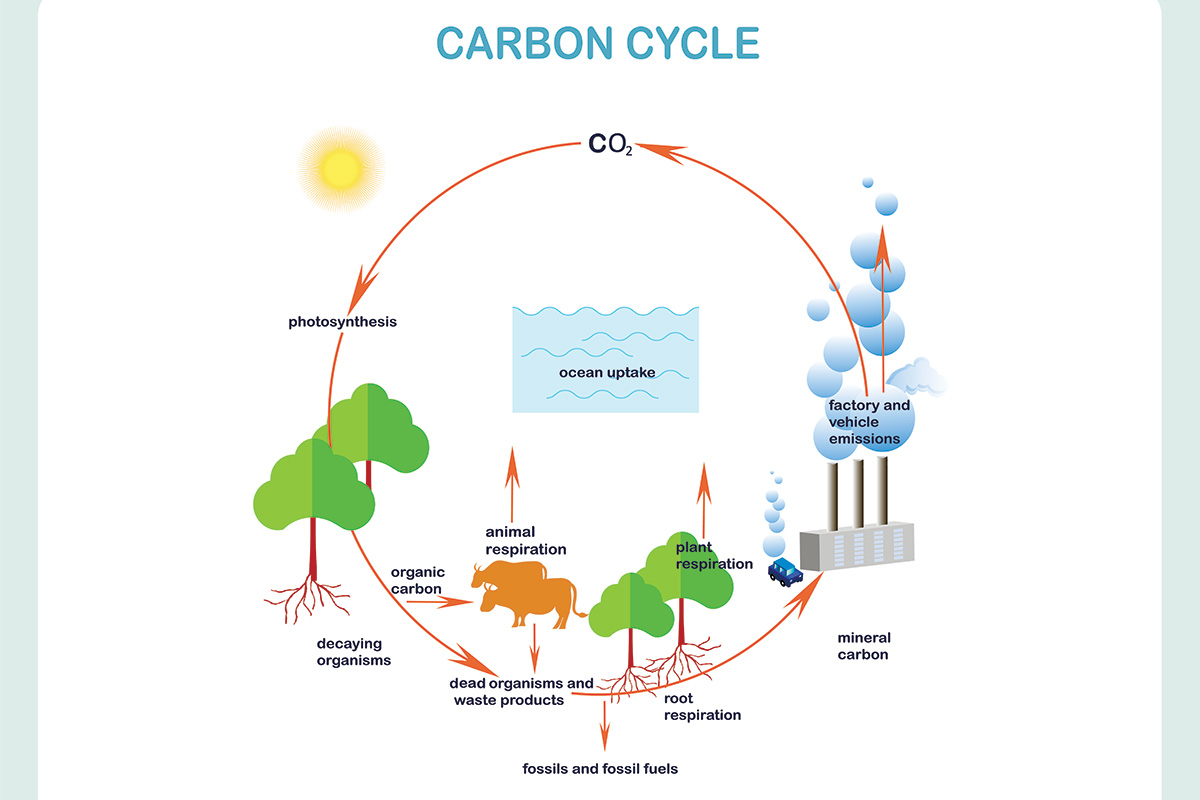

Plants also help mitigate the effect of climate change by taking in carbon from the atmosphere and locking it away. Plants absorb carbon dioxide during photosynthesis and store it in their leaves, shoots, and roots. Since carbon dioxide (CO2) is one of the main greenhouse gases that traps heat in the atmosphere, creating the “greenhouse” warming effect that the planet is currently experiencing, removing some of it benefits us all.

The Epidemic of Overgrazed Pastures

“Traditionally, people have taken a large tract of land [to graze their animals on],” explains Sandra Matheson, a beef producer and co-founder of Roots of Resilience, a collaboration of sustainability activists dedicated to the restoration of the world’s grasslands. (See more about Matheson below.) “People often just leave them out on the pasture until they run out of [grass]. Then they feed hay. They are left out there until the plants are gone, and it’s pretty much just dirt.”

Through her teachings, Matheson offers a paradigm shift to the pasture management approach, called holistic planned grazing. This begins with looking at the land from the grass plant’s perspective.

Grazing Recovery Time

“[Normally,] the grass is growing, the animal takes a bite,” says Matheson. “As time goes on, the animal goes back and bites the plant again and again because it’s sweet and tender.”

When this happens, the plant is using up its supply of energy in its roots. The grass needs leaves so the plant can photosynthesize and put energy back into the roots.

“If the animal keeps eating the leaves, then the plant loses roots and gets smaller, eventually dying,” she continues. “The plant’s recovery has been ignored. Planned grazing means having adequate recovery time after [the grazing animals] have bitten the grass.”

The rest period allows grass leaves to grow back so the plant will be able to photosynthesize and produce food for itself.

When overgrazing occurs, Matheson suggests it’s a function of time.

“It’s no longer a matter of animals per acre, it becomes a matter of timing,” she says. “In one month, they might have eaten all the good stuff, and all that’s left will be weeds going to seed.”

Matheson explains that plants need time to grow back leaves and replenish roots, adding that recovery time can vary with the season, climate, and soil type.

“It might be 30 days or maybe up to 90 days, or it might be a whole year,” she says. Recovery just needs to be enough time so that the plants grow back.

Matheson suggests allowing horses to graze an area until it is grazed down to about 3 inches, with the goal of not leaving animals out so long that the plants are bitten again after they try to regrow. Then remove the animals and allow the grass plants to recover and grow back to 6 or 12 inches.

“Plan grazing time so you have adequate recovery of the plants,” emphasizes Matheson. “That’s really the key here.”

Climate Resiliency

Climate change, or the ongoing increase in global average temperatures, is primarily attributed to an increase in carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. How do productive horse pastures help make for a more resilient climate?

“In the pasture we have soils and plants, and both are living entities,” says Sonia Hall, Ph.D., a research associate at Washington State University’s Center for Sustaining Agriculture and Natural Resources in Wenatchee, Wash. “One of the big things that moves through those living beings is carbon. Plants are able to move carbon through their biomass and transfer that to the soils, [which becomes] food for organisms in the soil.”

How much carbon pastures absorb “is very hard to accurately quantify,” says Hall, because the situation is so variable and depends on so many things. “But we do have some idea of how to move it in the right direction.”

Going back to the comparison of good pasture management versus poorly managed pastures, Hall says good pasture management allows plants to grow and add organic material to the soil.

“Don’t have your horses graze everything off,” she says. Echoing Matheson’s advice, Hall emphasizes proper recovery time for the plants.

“Graze, then give the plants a chance to recover and accumulate some reserves again, before you graze them again,” she says. Rotating grazing areas helps avoid overgrazing and moves horses to fresh pasture in response to how the plants are doing.

“Adding organic matter to the soil will help your soil become healthy,” adds Hall. On a horse pasture, this could be dead plant material (such as after mowing), straight manure, or compost.

In poor pasture management situations, according to Hall, the pasture is likely releasing more carbon into the atmosphere than the plants are absorbing, becoming a carbon source instead of a sink.

Sink vs. Source

“Your pasture is constantly taking up carbon dioxide from the air through plant photosynthesis and growth, and simultaneously releasing it through what the horses eat, digest, and breathe out, as well as through what the plants breathe out—yes, plants do that too!” says Hall.

Soil microbes and insects decompose and breathe out as well.

“If the carbon intakes through plant photosynthesis are more than what the horse, plants, and the soil breathe out, the pasture is accumulating carbon and is called a carbon sink,” says Hall, who refers to this as being “climate-friendly.”

When a horse overgrazes a pasture by taking grass plants down to the soil, then the plant can no longer photosynthesize as much and take in carbon from the atmosphere. If the amount of carbon that the horse, plants, and soil breathe out is larger than what the plants can capture through photosynthesis, then your pasture system is losing carbon to the air, and this is called a carbon source.

“If you have properly managed livestock on pasture, you are going to have healthier animals, more organic material in the soil, nutrients cycling through it, and increased biodiversity of plants there,” says Matheson.

Top 7 Tips for Horse Pasture Management

Healthy horse pastures don’t just happen; they are actively maintained with proper management practices. A well-managed grass pasture is one of the most cost-effective and nutritious feeds, and can be produced and fed by a horse owner.

Healthy pastures also support the goal of cleaner water by avoiding soil erosion and runoff of nutrients from manure and urine. Healthy pasture plants also reduce greenhouse gases by sequestering carbon. As a successful pasture manager, you are helping combat climate change.

Here are seven tips for keeping both grass plants and horses healthy with proper horse pasture management:

1. Establish a Confinement Area

Improve the health and productivity of your pastures by creating and using a paddock area where you confine your horses when they are not grazing pasture. You will be giving up the use of this land in grass production to benefit the rest of your pastures.

Confine your horses to this area during the winter and early spring when grass plants are dormant and soils are wet to help prevent soil compaction. In the summer, use the confinement area to keep pasture from being grazed below 3 or 4 inches, or any time when soils are saturated, such as during irrigation or storm events.

2. Keep Horses Off Soggy Soils

One of the most important aspects of horse pasture management is the time you keep your horses off pastures. Saturated soils are easily compacted, suffocating the roots of grass plants. A simple test is to walk out in your fields and see if you leave a footprint. If you do, it’s too wet for your horses.

3. Evaluate Current Soil Status with a Soil Test

How much compost or fertilizer you apply and the time of year you apply it should be based on the results of a soil test. Soil tests also determine if your soil’s pH will allow for plants to uptake nutrients, as well as if you need to fertilize, and the right mix of nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium.

Talk with your local conservation district or extension office for help on how to take a soil test, where to have it analyzed, and how to interpret the results.

4. Spread Compost

The best time to spread compost is in late spring or early fall—but anytime during the growing season is good. The nutrients, organic material, beneficial bacteria, and fungi in the compost will help your grass plants to become more productive and help your soils retain moisture.

Depending on the size of your pastures, compost can be spread by hand with a wheelbarrow and pitchfork or with a tractor and manure spreader. Go back through with a garden rake or harrow to spread compost into a thin layer so grass plants aren’t smothered.

5. Rotate Grazing Areas

By dividing a pasture area into smaller fields and rotating horses through them, you can encourage horses to graze more evenly, keep pasture grasses from becoming overgrazed, and provide fresh grass for a longer period during the growing season.

6. The Golden Rule of Grazing

Remember the golden rule of grazing: Never allow grass to be grazed shorter than 3 to 4 inches. This ensures that the grass plants will have enough reserves left after grazing to permit rapid regrowth. Consider the bottom 3 inches of grass an energy collector that needs to be left for the plant. Once horses have grazed most of the grass in a pasture area down to 3 or 4 inches, rotate them on to the next grazing area. You can put horses back on the first area when the grass has recovered and regrown to 6 to 8 inches.

7. Try Fencing Pastures According to Wetness

By fencing pastures according to how wet they are, in the spring you can let horses onto the higher, dry areas first and save the wet areas until later in the summer when they dry out.

Final Details for Horse Pasture Management

Make sure that pasture areas are large enough for horses to run and that gates are placed so that horses can easily be led from the confinement area to the pasture and back.

Remember to have a source of water for each grazing area. You can have separate water sources for each pasture or have a single water source that is accessible from more than one grazing area.

Also consider dividing the pasture in such a way that horses can have access to shade or shelter, especially if they will be in these areas for more than a few hours on hot summer days.

Meet the ExpertSandra Matheson is a beef producer in northwest Washington State. She owns 160 acres and pastures her animals on productive grasslands. Matheson is a retired veterinarian, a lifelong farmer-rancher, and an educator. She’s a Field Professional with the Savory Institute, an international non-profit organization established in 2009 with a global initiative to facilitate the large-scale regeneration of the world’s grasslands. She’s also the co-founder of Roots of Resilience, a collaboration of ranchers, farmers, university educators, and other sustainability activists dedicated to restoration of the world’s grasslands. Along with Roots of Resilience, Matheson helps run educational events, including week-long trainings for ranchers and land managers on sustainability and pasture management. |

This article about horse pasture management appeared in the September 2023 issue of Horse Illustrated magazine. Click here to subscribe!