We all have our own ways of dealing with stress, setbacks, relationship woes, demanding workloads and all of the effects these discomforts bring to our minds and bodies. There are countless ways humans will try to distract themselves, resulting in bad habits.

Without the ability to control their own feeding schedules or their environment, many horses can become sullen and aggressive as they develop behaviors from a past, ongoing or unchecked health issue.

Stable Vices

A vice is a practice, behavior, or habit generally considered bad or unhealthy.

Sue McDonnell, Ph.D., is a certified applied animal behaviorist and the founding head of the equine behavior program at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine. She shares that a horse who is exhibiting an undesirable behavior or stable vice that irritates and upsets his owner is not necessarily behaving badly.

“The veterinary scientific community has been trying to correct the misconception that horses intentionally choose to do these behaviors that are undesirable to people,” McDonnell says. “What owners are witnessing in their horse’s unwanted behaviors are coping mechanisms. The same goes for a human baby that is crying: We don’t think of the baby as evil or bad; [crying] just happens to be the only way a baby has to communicate or to cope with discomfort. Because we can’t always put a finger on why a baby is crying, a trial-and-error type of problem solving may have to take place.”

Owners have the same unfortunate issue; however, their baby is a 1,000-pound animal.

Messing with Nature

“We have taken the horse out of the wild, but we cannot take the wild out of the horse,” says Peter Morresey, BVSc, MVM, MACVSc, Dipl. ACT, Dipl. ACVIM, CVA, a shareholder at Rood and Riddle Equine Hospital in Lexington, Ky.

“Prior to domestication, the horse was a part of a free-ranging herd, grazing unconditionally, free to migrate to wherever resources and conditions were more favorable,” he continues. “Horses have been largely deprived of freedom of movement, herd social structure and transitioned to interval feeding. The nature of that feed has also radically changed: grass has been replaced by hay, concentrates with caloric and protein content are far above that was previously ingested [have been added], and roughage levels seemingly have been reduced.”

With all those major and minor variations and adjustments to the instinctive and inherent lives of horses, it’s no wonder they can sometimes have trouble adapting to the human-controlled versions of day-to-day functioning.

Behavioral History

Morresey’s first step into a horse’s medical evaluation is a detailed history, and he suggests documenting the timing of onset—the start of the behavior—its frequency, its manifestation, and any other events that affect how the horse displays the action.

“Things to consider are any changes in management, social structure, work level and in feeding,” he says. “Then you can progress to a thorough examination to see if there is a physical cause for the new or changed behavior. This can be extensive and take considerable time to document, but it’s well worth the effort when communicating with your veterinarian, equine behaviorist and nutritionist. The adequacy of stabling, feeding, turn out, tack and all materials that contact the horse directly or indirectly need to be assessed. A lameness, neurological oral, and ocular [eye] evaluation and an assessment for any muscular pain are essential to perform in order to gain as much information as possible.”

Both McDonnell and Morresey suggest that owners put their horse under 24-hour video surveillance to help determine a routine or cause of the behavior.

“The horse may display the behavior continuously, or only in the presence of the owner when an activity is anticipated,” McDonnell explains. She says that the video will also show how the horse budgets his time and the true progression of the behavior when humans aren’t in sight. Often behaviors seem to worsen or heighten when an owner or people are present.

Also read- Reduce Stable Stress

Orally Frustrated Behaviors

Cribbing is a repetitive behavior and apparent stable vice where the horse places his upper incisors against a horizontal hard surface while arching his neck and pulling backwards with his body while making a grunt inhaling sound. Windsucking is similar to cribbing but is done without the horse grasping onto an object with his teeth.

“Gastrointestinal issues that go untreated, like ulcers, can cause discomfort behaviors in horses, such as biting at objects, nuzzling at their ribcage or stomach area, and even cribbing,” says McDonnell.

“Obtaining a diagnosis by gastroscopy [an examination of the lining of the stomach using a flexible video endoscope] is highly recommended,” says Morresey.

Locomotive Behaviors

Pacing, circling, pawing, weaving and wall-kicking are usually observed in a stall, but sometimes can occur at the pasture fence, according to McDonnell.

“Weaving is a rhythmic side-to-side movement that can mimic an abbreviated form of perimeter pacing,” she says. “An even more abbreviated form is head-bobbing side to side. These actions can be a reaction to anxiety associated with confinement, separation and anticipation. They can be short-lived, ending once the situation subsides or is resolved.”

Pawing can start as a discomfort reaction when a horse wants to influence his environment but can’t due to confinement, being tied or isolated. It can also be caused by superficial irritation caused by ectoparasites: Lice living on legs, hair and especially in fetlock feathers can cause severe itching that will make a horse stomp, paw and rub.

“With time, these can become stereotypical and habitual behaviors that prove to be very difficult to treat due to the release of endorphins that take place when these actions are being done,” says McDonnell. “These behaviors generally aren’t damaging over short periods of time, but horses that are consistently performing these locomotive behaviors can have abnormal hoof wear, stress on their joints, uneven muscle development, performance problems and weight loss.”

Usually management improvements, such as offering the stalled horse frequent small meals of hay, ensuring turnout time and exercise, adding visual and social stimuli, regular parasite control and even having a friendly companion nearby, locomotive behaviors are reduced.

What Can You Do?

Morresey says that these behaviors require a multi-pronged approach due to the complexity of the condition and the non-controllable factors that encourage the behavior.

“Environment and social change need to be discussed with a veterinarian, and in many cases an equine behaviorist,” says Morresey. “Horses that have weaving tendencies can become addicted to the release of endorphins, just like any opiate.”

Possible treatments include calming agents, both medical and natural.

“Medications range from short and long-acting calmatives (e.g. reserpine, fluphenazine), progestins (e.g. altrenogest), and plant-based pharmaceuticals,” Morresey says. “Milk-derived proteins (caseins) have recently been introduced to the market. All have the ability to alter behavior in unfavorable ways and shouldn’t be dosed or given without veterinarian direction and consent.”

Whatever your horse’s unwanted behaviors may be, he’s just looking to calm the uncertainty of the unknown, ease his worries, and stop the discomforts that evolve and appear in life. Being a proactive, educated, and patient owner may not take the frustration away or fully prevent the behaviors, but it will help build a trusting bond with empathy and love for your horse, regardless of how he chooses to deal with challenges.

By ensuring he’s mentally and physically stimulated and providing positive reinforcement training and riding, pasture time, quality forage and consistent veterinary care, you can provide a pivotal role in helping your horse cope.

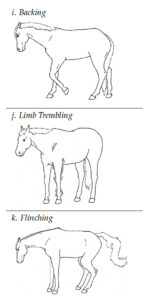

Measuring DiscomfortBy learning a horse’s body language and knowing what signs to pay attention to, you can learn what the underlying causes and conditions are behind horse behaviors and apparent stable vices. This could be the means to end mild to severe suffering, prolong longevity and promote an overall quality of life for your horse. Catherine Torcivia, VMD, and Sue McDonnell, Ph.D., Certified AAB, co-created the Equine Discomfort Ethogram that was published In the journal Animals in February 2021. Within the first week of posting, this scientific yet very reader-friendly tool was downloaded over 8,000 times.

Each of the 73 ethogram behavior entries is named, defined and accompanied by a line drawing illustration with links to online video-recorded examples where one or more horses are exhibiting each behavior. The objective of the ethogram is to describe behavior to owners and improve understanding, giving clarity to typical natural actions and abnormal behaviors. With this insight, horse owners, along with their veterinarian and equine behaviorist if needed, can address issues in mental and physical health as they maneuver around the necessary changes needed to support and treat their horse. To download the complete behavior ethogram, visit this journal. |

The inventory of discomfort-related behaviors observed has been compiled over 35 years of behavior research and clinical consulting services at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine’s equine hospital. It includes evaluations of thousands of hours of video recordings of hospitalized patients and many hundreds of normal healthy horses.

The inventory of discomfort-related behaviors observed has been compiled over 35 years of behavior research and clinical consulting services at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine’s equine hospital. It includes evaluations of thousands of hours of video recordings of hospitalized patients and many hundreds of normal healthy horses.