The ability to problem-solve is a key part of cognitive intelligence. Personal experiences and anecdotal stories show us that horses are capable of it. Many elements influence innovative behavior. Based on previous research, the scientists focused on age, sex, size, laterality (left or right “handedness,” often studied to establish if left- or right-dominant individuals are more successful at certain tasks), stress level, and task-

related behavior.

Design of the Study

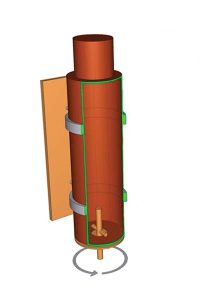

The horses were given 38 hours to empty, and thereby “solve” the feeder. The feeder was a casing tube with a rod attached at the base (see pg. 18). When nuzzled by the horse, the rod turned a crossbar on the interior of the tube, causing food to tumble into a collection plate. Further nudging shook the food into the horse’s feed trough. Through trial and error, the innovative horse could learn to manipulate the rod in order to receive the food reward.

◆ The motor laterality preference (“handedness”) of each horse was determined by researchers by observing them in pasture prior to the study. In horses, as in humans, the right side of the body coincides with the left hemisphere of the brain, which specializes in activities related to categorization and prior learning. The left side of the body—and right hemisphere of the brain—specializes in emotion, novelty, and social behavior.

Sensory laterality was marked by which eye was used when the horse made both an approach and contact with the feeder.

◆ Stress hormone levels, as measured by glucocorticoid concentrations (GCMs), were taken to establish the general level of stress of each horse.

Three samples were taken prior to the test to create a baseline. Another sample was taken on the second day of the test for comparison.

◆ Task-related behavior was recorded on two motion-activated camcorders during the study. The activity level of each horse was measured as the total amount of time the horse was in motion.

PERSISTENCE was defined as the number of times the horse’s muzzle touched the feeder, while TENACITY was defined by the amount of time the horse spent with the feeder.

LATENCY was measured as the length of time it took for the horse to make first contact with the feeder.

FOOD MOTIVATION was determined before the study began when each horse was given the same amount of food and timed. The amount of time that it took the horse to finish the feed was the measurement of food motivation.

Results Are In

The final results were clear:

◆ Four of the horses had completely emptied their feeder and could be called “innovative problem-solvers.”

◆ Six horses consumed only a portion of the feed and were considered “by-chance problem-solvers,” because it was not clear if they had learned to operate the feeder.

◆ The remaining six “non-problem-solver” horses did not obtain food from the feeder.

The researchers found that age, stress hormone levels from the test day, persistence, food motivation, and height could be eliminated, and sensory and motor laterality could not be fully considered as a factor, because most horses in this study tended to favor their left side.

The researchers did note, however, that all of the four innovative problem-solvers had “significantly higher” left motor preference, and three of the four had similarly higher left sensory scores.

Sex played an interesting role. While the four problem-solving horses were split evenly—two mares and two geldings, all of the by-chance problem-solvers were geldings, and all of the non-problem-solvers were mares.

Final Analysis

In the final analysis, four traits stood out: activity, latency, tenacity, and a high baseline stress hormone level.

In general, successful horses were very active, and they spent the most time engaging with the feeder. Ironically, they were considerably slower to first approach the feeder.

The researchers deemed this combination a sign of inhibitory control—a cognitive process that allows the horse to adjust each try based on past success or failure and hone in on only successful actions.

From this trait combination, the researchers concluded that innovative problem-solvers were “active, tenacious, and have a higher inhibitory control.” Successful horses also tended to be more emotional based on “high baseline stress hormone concentration and a strong left [handedness].” That strong left-side dominance was taken into account as an indicator that problem-solvers saw the problem through the lens of the more emotional right brain.

The researchers suggest these last two traits may be the result of life experiences in which the horses have been exposed to a variety of challenges and activities that required similar problem-solving. They hope that their work will lead to more study and a deeper understanding of the cognitive capabilities of horses.

This article about how horses problem solve appeared in the September 2020 issue of Horse Illustrated magazine. Click here to subscribe!