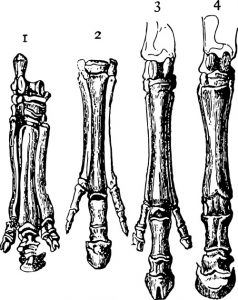

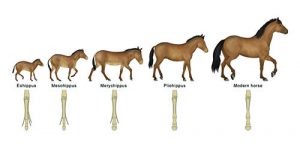

The earliest horses were tiny woodland creatures, the size of a housecat or small dog. They had a springy back and (usually) four toes in the front and three toes in the back. Over millions of years, as the horse grew in power and strength, those toes slowly disappeared. This left one middle digit—the hoof.

But a recent study published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution begs to differ. After looking long and hard at fossil records and prior research, the authors say that though horses are able to pick up speed when needed, their physiology tells a different story: Horses, they posit, are more suited to trotting—not in retreat—but in pursuit of food.

Mechanics of the Leg

While most prior work has focused directly on the hoof, this study took a wider view by looking at the entire leg of the horse. While the three-toed horse had a similar leg makeup as the hoofed horse, it was really the hoofed horse that has an optimal leg in a mechanical sense.

The interior of the hoofed horse leg is an intricate conglomeration of ligaments, tendons, and bones that work in synchrony to create elastic energy that is stored and released as the horse propels forward. Aptly named the “spring leg,” the effortless strength of the horse’s leg is the real source of its incredible power.

The fetlock joint, as it is winched downward by force when the horse moves, acts like a rubber band or a spring when released. The fetlock is incredibly flexible, capable of stretching down to 90 degrees from vertical. This construction, note the researchers, is the real key to the survival of the horse.

Not only does it allow for tremendous power, but it’s also extremely efficient because the snapping back action, like that of a bow and arrow, is a passive movement that requires less metabolic stores of energy.

The authors assert that though energy is saved this way at all gaits, it is at the trot that the horse is most efficient—leading them to solidify their hypothesis that horses are well-equipped to spend most of their time trotting across long distances in search of grazing lands.

Working with the Back

In addition, the anatomy of the horse’s back confirms this conclusion. By this time period, the horse had evolved to have a shorter, firmer, and less flexible back. Flexibility in the back would also provide elastic energy and is necessary when horses run at high speeds, as the back end of the horse curves under to take long strides.

But a less-flexible back, when combined with more spring-like legs, would not hinder the more vertical movement seen when a horse is trotting. The authors evidence this by the fact that horses in the wild trot naturally across grassland, endurance riders often utilize the trot, and even the U.S. Cavalry preferred the trot as a form of efficient travel.

It is convincing that an energy efficient leg and a sturdier back would enable the horse the required endurance that would be necessary to search for food. But what was confounding for the researchers is that the three-toed horse also had a spring leg, and even though it was less developed, the question remained, why did the hoofed horse eventually become the sole survivor while the three-toed horse became extinct?

Changing Climate

The researchers next looked at climate. The one-toed horse first appeared in North America approximately 15 million years ago during the late Miocene era. This was a time of warm, moist temperate weather in which three-toed horses and hoofed horses both thrived and lived alongside each other.

The landscape was primarily woodlands, which provided ample food sources for a variety of horse species. Three-toed horses were thought to have an advantage in muddy footing, with their extra toes providing them better balance and maneuverability. At this point, hoofed horses were just a small part of a larger, richly diverse group of horses—most of which remained three-toed.

Over the next 10 million years, the three-toed horse began to decrease in size and diversity as significant weather changes occurred. The climate became drier, colder, and less hospitable. As arid grasslands replaced fertile woodland, three-toed horses found their preferred habitat continually shrinking to the southern regions.

(ALDONA GRISKEVICIENE/SHUTTERSTOCK)

One-toed horses, with that stronger, more efficient leg, had a much wider territory to choose from, and their foraging behavior, which prioritized the more prevalent grasses, followed suit. By 1 million years ago, only hoofed horses remained as all other horse species gradually disappeared.

The authors of this study rest on the conclusion that the hoofed horse evolved not because the single hoof had any particular advantage over the three-toed horse, but because climate change created an environment that allowed this horse, with its already built-in efficiency of locomotion, to take advantage of a larger range of foraging.

Their perspective is that the hoof, along with the superior leg, encouraged the hoofed horse to travel long distances. This ability to roam and rely on grass as a food source inevitably helped them survive while others went extinct.

In the author’s own words, “Equus was fundamentally a lucky genus in the grand scheme of equid evolution.”

Source: www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2019.00119/full

This article originally appeared in the July 2019 issue of Horse Illustrated magazine. Click here to subscribe!