Your horse isn’t going to need a great deal of additional work over fences before you go to a show. In fact, whether you’ll be competing your horse in the hunter, the equitation, or the jumper division, it’s entirely too easy to school too much and overdo your preparation over jumps. Remember, he knows how to jump. While he does depend on you to establish pace and direction, what he needs you to do most is stay out of his way and let him do his job.

In the show ring, he probably won’t just meet “plain vanilla” fences, so make the obstacles you take him over now a little interesting: use some color, drag in a flower box or two, include a liverpool if you’re on a jumper. The more varied the elements he meets now, the better off he’ll be when you show him.

The Right Warm Up

If you’ve been doing your flatwork consistently and correctly, warming your horse up for this jumping school is really just a matter of making sure he’s relaxed and loose and on the aids—it’s suppling, not training, like the preliminary stretching a runner or swimmer does before getting down to work.

It’s also your opportunity to set the tone for the day, which should be, “Today we’re going out to jump; it’s going to be fun!” No dressage, no drilling. If you were working through a difficult problem yesterday and didn’t quite get it solved, let it alone for today.

If your horse is the hot, excitable type, though, be sure he gets turned out or give him 10 minutes or so on the longe to get the bucks out and relax him before you start the school. If he’s excited, you’ll get excited—something I see all the time with riders who come to my clinics—and neither of you will pay enough attention to the school to benefit from it.

Ten or 12 minutes is probably enough for your warm-up (although you can certainly do a couple of minutes more if you’re still feeling stiffness). Start with a couple of minutes at the walk. Then go on to the trot and do some lengthening, some shortening, a little lateral work—just enough to review basic skills, check responses, and loosen up any stiff spots; you’re not asking for his best dressage—that can wait for your next flat session. (But if your horse tends to be stiff on the right, for example, do a little right shoulder-in.) Follow with a couple of minutes in the canter—just enough to get the edge off. Before you start jumping, you should feel him being round, light, “in your hand,” “on the aids”—which won’t take long now because of all the days you’ve put in on the flat.

Starting Off

This jumping school is for you as well as your horse, of course. From the warm-up to the end, keep thinking, “Eyes up, heels down,” and work on keeping your position correct, supple, and relaxed. Don’t let yourself get excited about the jumps—your horse knows how to do them, remember?—but focus on position, pace, and rhythm.

If you’re on a quick, hot horse, think, “Slow, slow, slow”; your body language will carry the message to him. If your horse is the lazy, dead type, think of a quicker, more active rhythm. Be sure you stay calm and relaxed.

Begin the actual school by trotting a few very low obstacles—a pole on the ground, a brush box, a little cavalletti—focusing on keeping your horse straight and forward. Then make sure your turning aids are working: go over one or two of them again, this time turning to the left over the obstacle; then once more turning to the right. Be conscious of how you’re using your eyes.

Now trot a couple of fences with a little more height (at least 2′)—a cross-rail, a low wall, or a low vertical—to make sure your horse is relaxed and smooth and maintaining an even rhythm. He should trot all the way to the bottom of the jump and stay very, very straight.

Canter those same low jumps now, concentrating on keeping a steady rhythm. Meet them straight first, then on a little angle; stay very relaxed—and maybe even relax your contact at the takeoff if your horse is confident enough.

Stop once or twice on a line after the fence; then to encourage suppleness if you’re on either a hunter or a jumper, make a couple of turns following the landing, left and right—and try not to make a big issue out of it.

From single fences, go on to a few lines that pose questions, as the lines in my jumping exercises have done. Depending on the division in which you’ll be competing (see the variations that follow for more specifics), ask the horse to lengthen, or shorten, or both (in a three-element line); use verticals and oxers, straight lines and bending lines; add strides, leave strides out; make an oxer-to-vertical into a vertical-to-oxer by circling around and riding the line in reverse.

Make the fences just a little more challenging by raising the rails a couple of holes or widening the oxers a few inches—limited equipment doesn’t have to mean lack of variety. You don’t have to do much; you’re just reminding the horse of what he knows how to do.

Basically, you should remember from the earlier work you’ve done what your strong and weak areas are. Work on your weaknesses—if it’s your eyes and turns, do more circles; if it’s that generally you go too slow to your first fence, practice pace and soft hands. Know your horse and yourself so that you go to the warm-up with a plan of what you need to do to produce your best effort in the ring.

Variations For Your Discipline

For Hunter Classes: Set up lines similar to those you’re likely to find at the show. Raise a few of the fences to the height he’ll be meeting, with distances between on a normal 12-foot stride, especially if you’re competing in junior or amateur classes. On an older horse, or one being prepared for regular working classes, you may want to keep him sharp by lengthening a few distances a foot or two. Practice the lines over and over—not pulling up after each one, but just as you’d ride them at a show, continuing and maintaining a good rhythm.

For Equitation: Your horse will be meeting more challenges than the hunter will, so do more with adding and leaving out strides, riding different options to the same fence, approaching on turns, and landing and turning. Run down your list of skills—eyes, hands, seat, lengthening, shortening, jumping off turns.

For Jumper Classes: While I would make the jumps a bit bigger and tougher if I were preparing a horse for a big, important competition, for regular jumper classes I keep the school simple and relaxed and the fences not too big. I might include a liverpool, a square oxer, a distance or two as much as 6 feet off normal, and some fairly gymnastic combinations, but I’d he careful not to overtrain or overface the horse.

No matter what the discipline or the level, the overall feel of your jumping school should be very relaxed. Certainly the more advanced you and your horse are, the more challenging your practice can be. But be smart. You want to remind your horse of how to do what he knows how to do correctly, not challenge him or yourself to do something new or different.

Generally, any time you’re going to a competition, a positive feeling is very important.

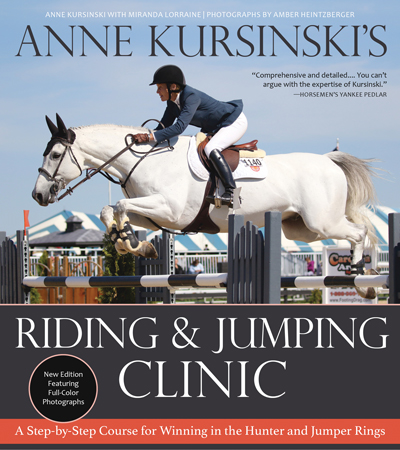

This excerpt from the new edition of Anne Kursinski’s Riding & Jumping Clinic by Anne Kursinski with Miranda Lorraine is reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books.

This article on prepping your jumping horse and how not to school too much appeared in the June 2020 issue of Horse Illustrated magazine. Click here to subscribe!