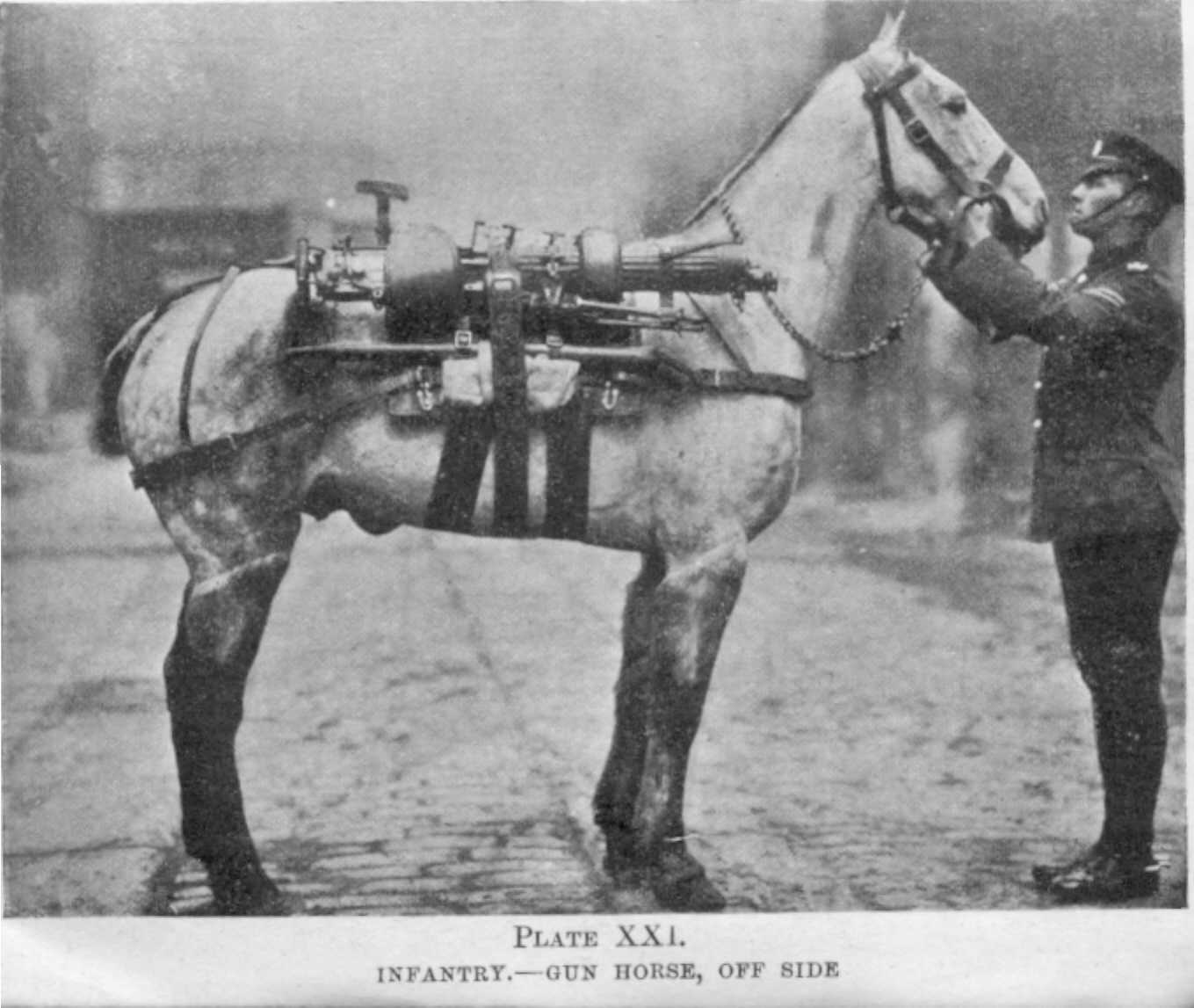

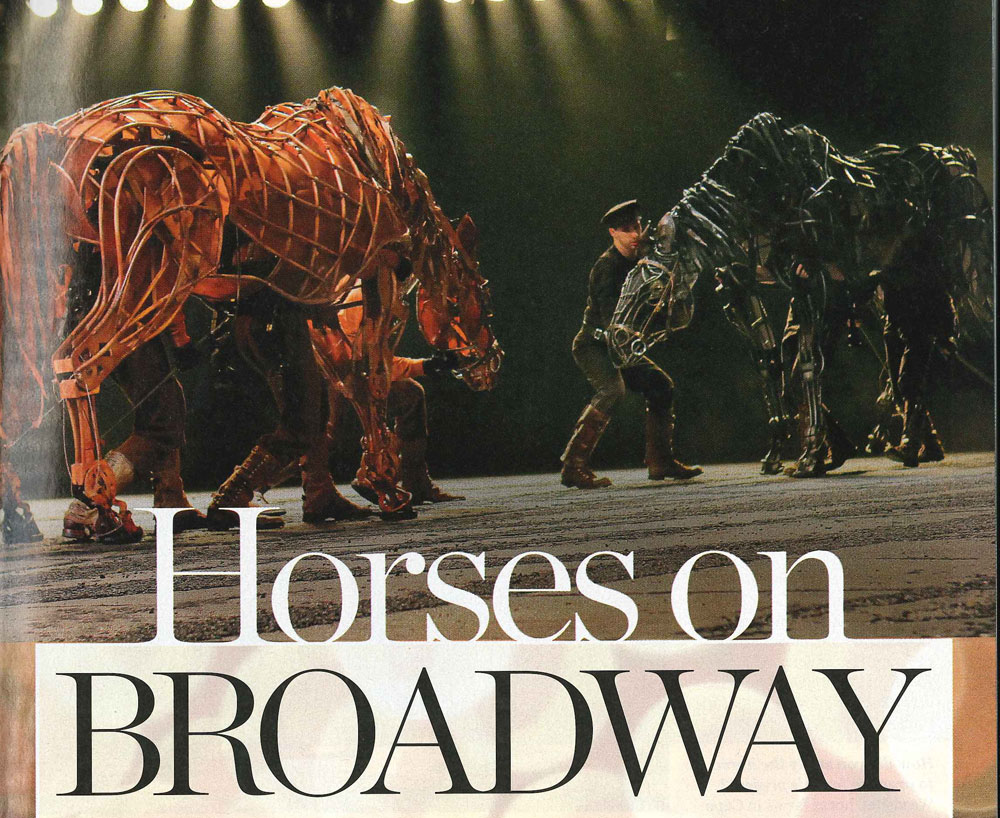

This morning, Veteran’s Day, I saw a picture on Facebook that honored the 8 million horses that died during World War I. The blurry, black and white image took me back a few years to seeing the play War Horse on Broadway. It was such a thrill to “meet” those heroic horses up close and interview a few of the actors backstage. Seeing that play was a real education in how theater uses the imagination of the people in the audience. Yes, they were puppets, but each breath and each stride brought them to life, for real, on stage. Brilliant! This is the story I wrote about the experience.

“In the beginning of the play, you notice the puppeteers but then you see just a horse and you invest in his journey,” says War Horse actor Joel Reuben Ganz, who serves as Topthorn’s “heart” and front legs from inside the puppet’s aluminum frame. “When the horse hits the ground and the puppeteers leave, it’s like a real death.” Working the horse puppet takes two other actors in addition to Ganz – Jonathan Christopher MacMillan at his head and Tom Lee who, also inside the puppet, moves Topthorn’s back legs with two hand-controlled grips. Lee uses a dial to swish the tail up or side to side.

The hit Broadway play WarHorse brings to life the thrilling story of young Albert Narracott and his beloved horse, Joey. They grow up together on a farm in rural England and endure the heartbreak of separation when Albert’s father sells Joey to the military. Sixteen-year old Albert lies about his age, joins the military and journeys across England, Germany and France to find his horse.

Adrian Kohler (along with collaborator Basil Jones) created the puppets for the play with the intention of portraying the equine characters as real horses on stage, not people in disguise. The name of their company, the Handspring Puppet Company, which Kohler and Jones founded in Cape Town, South Africa in 1981, suggests just how the actors bring life to these beautiful stage creatures.

“I learned from a very influential Russian puppeteer,” says Kohler, “that the soul of the puppet lies in the palm of the hand, meaning direct-controlled figures versus indirectly controlled string puppets.” On stage, with help from actors like Ganz, MacMillan and Lee, the horses breathe, whinny, flick their tails, and spook in reaction to what’s happening on stage. At one point, the huge, bay Joey thunders up the stairs through the audience.

“Really it’s the audience’s imagination that completes our performance,” says Lee. “The horses on stage are magical.” Where does the magic behind the puppets come from? Horse Illustrated contributor Kitson Jazynka chatted with Kohler to find out.

How did you study the horse to prepare for this project?

We visited horse farms in Cape Town and England trying to find out about relationships between horses. In Michael Morpurgo’s book, War Horse, which the play is based on, the horses talk to each other. We needed details about horses communicating. But we had to do it nonverbally because we didn’t want talking horses on stage. We heard a story about a horse that had pinned another horse up against a wall. He was thought to be a bully, but it turns out that the horse that was being pushed against the wall couldn’t stand. The other horse had been supporting his companion. We used that moment in the play when Topthorn dies and Joey tries to push him up with his neck. We also studied Monty Roberts’ work.

What was the biggest lesson learned from Monty Roberts?

That the horse is a flight animal and if you want to get close, you have to offer him your side, not direct eye contact. We used that a lot in the play, like when Albert first meets Joey as a foal.

What aspects of the horse were the most important to portray in the puppets?

The hoof movement, tail movement and ear movement were vital to get right. When you hear a horse walking on a paved road – if you can get that sound sequence right, even if it’s not a real horse, the audience immediately makes the jump that it’s a horse. We figured out walk, trot and gallop with the puppets, but not canter. It was too difficult to get three feet off the ground at the same time. The ear movement was difficult because I wanted them to move 180 degrees. This way they could point forward for curious and backwards for fear and anger. The tail, made of a synthetic paper that catches the air, is controlled by three tendons, one that pulls left, one for right and one for up. Gravity pulls it down.

What was the biggest challenge in making the puppets?

The hardest part was making the puppets horse-like enough yet with enough space for two people to work inside.

What is your favorite part about making the puppets?

I love the teamwork. The puppeteers are extraordinarily dedicated and they make the horse come alive. And in Cape Town we have a very dedicated team of puppet makers, who sculpt the aluminum frames, make the ribs out of stretched cane and bind them to the frame with waxed thread. It takes a lot of patience and wear and tear on their hands, yet they love it. We had an enormous fireworks display when they sent all the puppets off to New York. The horses leaving left quite a hole in our factory.

For more information about the War Horse, check out handspringpuppet.co.za.

Back to Over the Fence

Follow Kitson Jazynka on Twitter: @KitsonJ.