For horse owners, finding an equine vet you trust—and one your horse trusts—can be a daunting task. In years past, finding a good match might involve multiple meet-and-greets with vets and equine clinics to review your horse’s health and history. But today, in many areas of the country, the ability to choose from multiple vets isn’t an option, even if you don’t see eye to eye or agree with the pricing structure of the practice located closest to you. In fact, the shortage of equine vets in rural areas is reaching a crisis point—and horses will be the ones to pay the price. Veterinarians, vet schools, and equine-health organizations like the American Association for Equine Practitioners (AAEP) have been sounding the alarm for years that this issue would soon reach a breaking point.

Sobering Statistics

Taken more broadly, the rural vet shortage translates into a shortage of large-animal and equine vets throughout the United States. Amy Grice, VMD, a veterinary business consultant in Virginia City, Mont., and current treasurer of the AAEP, notes that well under 2 percent of vet school graduates take equine practice associate positions each year.

This means that of the 4,000 veterinary graduates each year, fewer than 50 take equine associate positions, although about 100 additional graduates begin internships in equine-specific fields of practice. Add to this the nearly 60 equine veterinarians retiring each year—which is expected to grow by 3 percent per year—and the chasm widens even more.

If that’s not startling enough, this should be: Nearly half of the new vet school graduates who begin working as equine practitioners are not working with horses five years after they graduate.

Why Vets are Leaving

Multiple factors play into many vets’ decision to forgo the equine side of veterinary medicine—and why they leave. Often cited are:

◆ Lack of work/life balance

◆ Frequent on-call time

◆ High stress

◆ Low pay

It’s important to consider that the more rural the service area, the more pressing these issues are likely to be. While vets at larger, equine-only clinics—usually in or near bigger cities—can often offer more pay and specific working hours, doctors further from equine medical hubs are often on call 24/7/365 and earn lower salaries.

With few graduates interested in working in more remote areas, it’s understandable why some equine practitioners feel the only way to have a better work/life balance—and all that entails—is to leave equine vet med entirely.

The draw to companion animal medicine is real: Better pay (the average starting salary for an equine vet is about half what a companion animal vet makes), limited or no emergency duty, and shorter work weeks are all enticing, specifically to veterinarians who might be interested in starting and spending time with a family.

The Work-Life Balance Struggle

Though designed to make life easier, smartphones have been both a blessing and curse to equine veterinarians. The ability to snap a pic and send it to the vet has alleviated many unnecessary farm calls, but it also comes with an expectation of vets being “always on.”

Some horse owners expect near-instant responses to texts, calls, and emails, forgetting that not every vet has a technician with them to free up time for rapid-fire replies. Though it can be easy to forget that vets have more than one client when your horse is in the throes of an emergency, it’s critical that you allow them some time to respond.

“Setting boundaries [for clients] early is essential,” says Rhonda Rathgeber, Ph.D., DVM, of Hagyard Equine Medical Institute. Vets letting clients know in advance when they will be unavailable is also helpful, as is providing contact information for an available vet.

Though a horse owner may think “it’s just a text,” it’s important to realize that the expectation of a response—often for which they aren’t getting paid—adds to the feeling that vets must be accessible 24/7. To alleviate the angst this immediate-response mentality might cause, ask your vet what time of day is appropriate to text or call—as well as how long it might take to get a response.

To keep vets practicing in the field, it’s important for you as a client to help set them up for success.

Financial Assistance Programs

For those not entrenched in equine veterinary medicine, it can seem that not much is being done to address the vet shortage issue from a national scale, but multiple programs and initiatives have been enacted to try to encourage more vets to relocate into rural areas.

One of these is the Veterinary Medicine Loan Repayment Program (VMLRP). This program will pay up to $25,000 a year for three years toward the student loans of vets working in areas designated by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA, part of the USDA) as “shortage areas.” The vet must work in such an area for a minimum of three years to receive the $75,000 loan repayment.

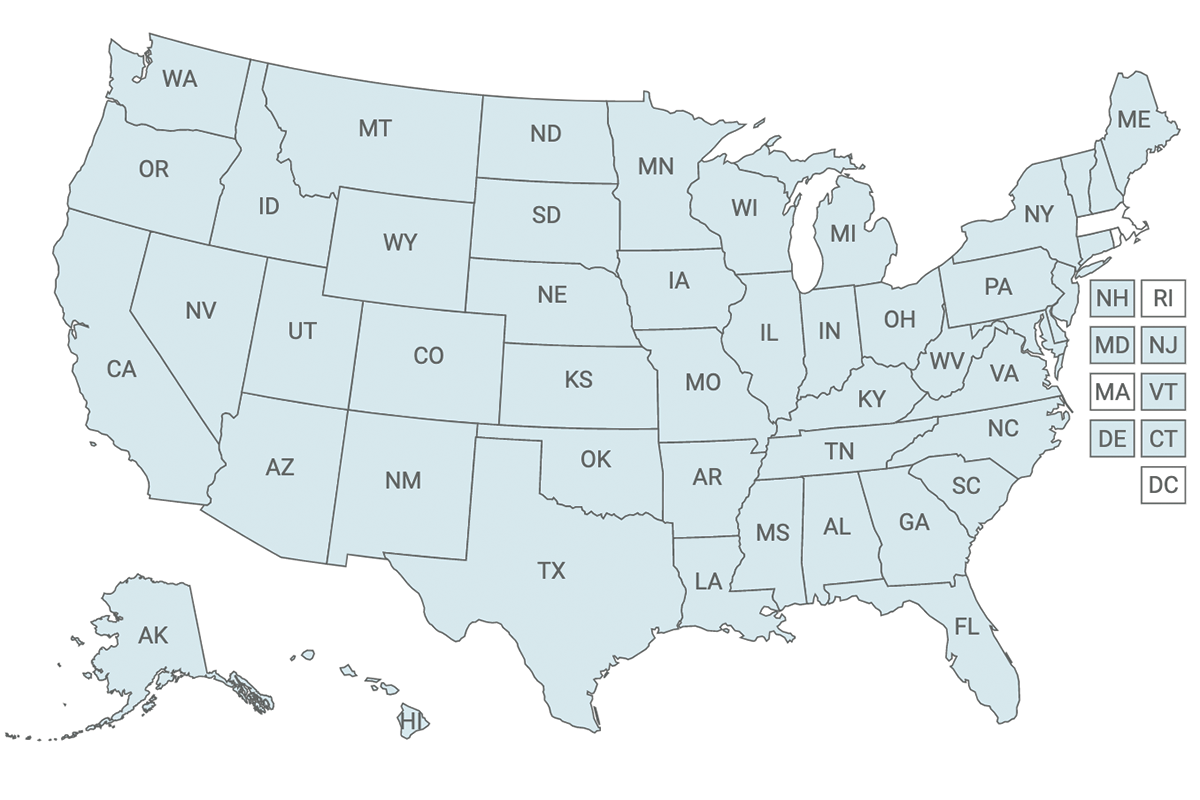

The NIFA creates a Veterinarian Shortage Situations map each year. At press, there are only two states that don’t have rural vet shortages: Massachusetts and Rhode Island, as well as the District of Columbia.

Interested veterinarians may apply for the VMLRP grant; once funding is given, the applicant must secure employment in a rural clinic within 90 days. At the conclusion of three years, a vet working in a shortage area can apply for a VMLRP extension for as long as he or she still has veterinary school debt. While this program doesn’t address the salary of an equine veterinarian, its use will hopefully alleviate some of the stress of mounting student loan debt.

However, this program has its pitfalls: Both the loan and tax payments made on the VMLRP recipient’s behalf are considered taxable income by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). This means that this grant could increase federal taxes, and possibly state and local taxes, owed by the recipient. To offset these potential taxes, VMLRP provides supplementary funds.

An additional financial assistance program available is the Veterinary Services Grant Program (VSGP), which provides grants to entities that carry out programs or activities that develop, implement, and sustain veterinary services through education, training, recruitment, placement, and retention of veterinarians and vet students. Grants are available to private practices, nonprofits, and veterinary schools, and can be used to establish or expand veterinary practices.

Other Solutions

However, addressing student debt alone won’t solve all vet shortages—nor will simply churning out more equine veterinarians, as logical as this may seem. The innate lack of a work/life balance, and the stress that it creates, will still be the root cause of reluctance for vets to join or stay in equine practice. Wellbeing and mental health are directly tied to stress and its management. Burnout is real and is taking its toll on the veterinary population.

Many vets who start as part of an equine practice eventually strike out on their own. Though security is a draw for recent graduates, many eventually find themselves unhappy with certain aspects of their job or their employer. Opening their own practice allows them to create new business models and a work culture that best suits their lives.

Some new practices are working to create businesses that will entice future generations of vets. Many focus on sharing emergency duties with other clinics, creating clear work/life boundaries that alleviate some of the 24/7 work mentality, and networking to build a social support structure.

The AAEP is also working diligently to address the attraction and retention of equine veterinarians. A task force has been created to identify the issues in equine veterinary medicine and explore ways to solve them. It is hoped that through honest discussion, real, actionable processes will be determined and implemented.

The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) is deeply vested in determining why fewer students are choosing veterinary medicine and remedying the problem. One proposed solution is the implementation of two new, credentialed veterinary professional roles: One that works under a veterinarian to diagnose, prognose, prescribe, and perform surgery at a limited level and a second role related to clinic management.

The goal of these new roles would be to improve efficiency and reduce workforce stress. Thus far, there has been no analysis done to determine if these professional roles are needed, or how they would differ from already established roles. Despite this, efforts to create an educational framework for these roles are ongoing. AVMA is researching if these additional team members are needed and whether they will positively affect the work/life balance that is currently lacking in so many aspects of veterinary medicine.

Enticing Vets

Though many equine vets eventually strike out on their own, practices with open positions are offering a plethora of perks to entice vets to join their communities.

Rhonda Rathgeber, Ph.D., DVM, has been an equine veterinarian with Hagyard Equine Medical Institute in Lexington, Ky., for 26 years. She was the internship coordinator for the clinic for 17 years and has seen many changes in the equine veterinary world, including on the employment side.

“We used to have 60-plus applications for our internship program [each year],” Rathgeber says. She notes that this number has declined significantly, though COVID most likely played a role in the reduction in applications the last two years.

This startling decline in applicants is not unique to equine-centric Kentucky; many clinics and practicing vets are trying all manner of incentives to attract equine vets to their area, including everything from signing bonuses to the promise of practice ownership when the lead vet retires.

Hagyard offers housing and housing allowances to new vets, says Rathgeber, but now they are also offering more time off as well as opportunities for vets to expand their skills.

“[New vets] have rounds and lectures and labs to practice their diagnostic skills,” she explains. “They have an assigned team of mentors in addition to the 40 veterinarians on staff, and they rotate through each department. They palpate behind a reproductive veterinarian and learn the booking process, and they get time for continuing education and a stipend for it.”

Even these added enticements aren’t enough to fill all the equine vet vacancies in Kentucky—and the same story is repeated at clinics and practices around the United States.

As the industry works diligently to fix the decline of the equine vet workforce, horse owners and caretakers have their own role to play (see “Why Haven’t You Replied?”, left). Understanding there may be a delay in care because of overwhelming caseloads and offering compassion are just two ways to show practicing vets that horse owners care. Being aware of time constraints and each vet’s right to personal time is another.

Horse owners, veterinarians, and equine organizations must work together to address burnout in equine veterinarians. If they don’t, it’s horses that will end up suffering.

This article about the equine vet shortage appeared in the March 2022 issue of Horse Illustrated magazine. Click here to subscribe!