Safe or Unsafe?

The human brain takes a giant dataset and compares it with information saved from previous experiences. Then it decides whether you are SAFE or UNSAFE. If your brain assesses the coming situation to be SAFE, it will relax your muscles, reduce your respiratory rate, keep your heart rate steady, and allow your joints to move through their full range of motion.

However, if it assesses the coming situation to be UNSAFE, it will increase muscular tension, respiratory rate, and pulse rate, and you might also experience pain or shortness of breath. Many people experience back pain. What’s more, your mental state is instantly influenced by your brain, so you feel anxious. And if your brain keeps detecting UNSAFE situations, you might even become depressed, which serves to avoid threats and keep you safe.

Perception of Safety

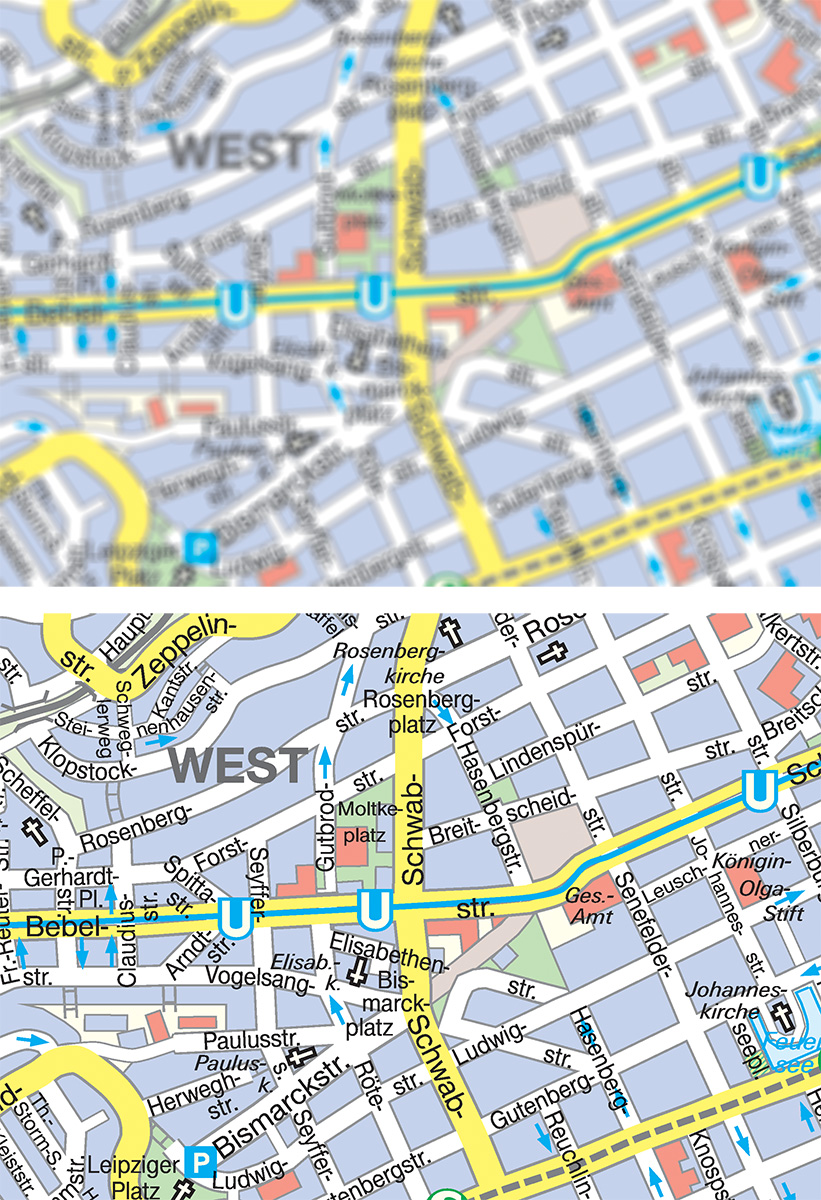

All this means we need to find stimuli that increase our perception of our safety. I’d like to use an example to explain what that means in practical terms: Imagine you tear a ligament in your ankle and rest your ankle for a long time. Your brain hardly receives any signals from the motion sensors in your ankle while you’re resting it. The neurons that transfer information from your ankle to your brain are “asleep” and may be asleep for weeks. When neurons stop firing, their connections to each other become weaker. Prior to your injury, the “map” of your ankle in your brain was precise (see clear map image) but now, after weeks without any activity, it isn’t precise anymore (see blurry map image).

That means your brain no longer knows exactly what position your foot is in; as a result, it can’t accurately predict how the foot can bear weight. Is this a good starting point for your brain to ensure your “survival”? Nope! Your brain thinks: “I have no idea what the foot’s doing, so I can’t guarantee anything.” In this context, riding your horse at canter over a log is immediately categorized as UNSAFE, and full power to your body and riding position will not be made available. But that obviously applies to all movements, not just jumping a log.

And if you nevertheless decide to jump the log, despite your brain’s hesitation, your stubborn frontal lobe will go on an ego trip. It can work, but only because people are incredibly good at compensating. You can expect your brain to reach for its ultimate emergency brake: pain. But you shouldn’t resent it, because it’s just trying to protect you. Your brain produces pain because it believes there are too many threatening signals and too few safe signals (G. Lorimer Moseley 2017).

Input and Output◆ The brain’s most important job is to keep us safe. Safety always comes before performance! |

When the Nervous System Takes It Too Far

Anxiety about riding is something riders don’t like to talk about. Everything becomes less fun, becomes a test of courage, and we start avoiding things that trigger our anxiety. We communicate our anxiety to the horse, too. Anxiety makes us overreact and sometimes do strange things—and often those things cause the horse to suffer. But our anxiety is usually based on false assumptions and expectations about future events. We can be anxious about people, animals, things, situations, movements, and pain. Denying or not acknowledging anxiety unfortunately doesn’t make the problem any smaller. Quite the opposite.

It’s much more helpful to recognize and understand anxiety. The leading scientist in the field of anxiety research, Joseph LeDoux, once said: “Anxiety is the price we pay for our brain’s ability to imagine the future.” I think that sums it up quite well.

Lorimer Moseley from Australia is one of the world’s leading scientists looking into the question of what pain is, how pain arises, and, of course, how we can reduce pain. He concisely sums up the results of his research: “Pain is a construct of the brain” (L. Moseley 2011).

Top researchers from both fields agree that pain and anxiety are “output”—that is, they are our brain’s opinions about the state of the current and future dangerous situation in and around our body.

In the case of fear of heights and vertigo, there are experimental indications that this unpleasant feeling could result from an “intersensory maladjustment if visual information does not correspond to vestibular and proprioceptive information” (Brandt et al. 1980).

It goes without saying that our experiences play a major role in this subconscious formation of opinions, as does the social and cultural milieu that we live in. Context influences perception of anxiety and pain (G. L. Moseley and Arntz 2007). For example, one and the same movement can occur and cause distress in the context of “barn/horses,” but cause no distress in the context of “family” or “office”—or vice versa.

Pain (and equally anxiety) warns us about impending danger and the threat of pain, and immediately mobilizes our stress and emergency systems to arm us against that potential threat. However, anxiety and pain aren’t necessarily proportional to the degree of actual injury, actual physical harm, or actual threat or danger we’re experiencing: We can feel incredible anxiety, capable of paralyzing us, even without being attacked by a real tiger. Knowing there’s no realistic chance of falling doesn’t stop us from feeling fear of heights. And in the same way, we can feel intense pain even when nothing is wrong. On the one hand, pain and anxiety are important, self-protective feelings—on the other hand, they can be disruptive and unhelpful when they occur frequently and inappropriately. Excitingly, numerous pieces of research show that understanding how these feelings arise can greatly reduce pain and anxiety. Knowledge can therefore be a very effective painkiller and anxiolytic (G. L. Moseley 2004)—and now you know a little more.

Allies for Survival

It’s helpful to imagine anxiety and pain as friends and allies, because, after all, they only want us to survive. However, sometimes these feelings objectively aren’t appropriate to the situation.

A mouse in the tack room is just as unlikely to kill us as a papercut, but both can trigger strong emotions. Pain can become problematic when an injury has long since healed, or when there is objectively no threat. Our “protective system” is working overtime, and protects us unnecessarily, like a “helicopter parent” at the playground, always hovering over their child, ready to needlessly intervene in a game and deny their child opportunities to learn. Many different areas of the brain are involved in these reactions. In pain research, we talk about the “pain neuromatrix” (Melzack, n.d.; G. Lorimer Moseley 2017; Chapman 1996; Legrain et al. 2011).

Neuromatrix

Let’s take an example: Imagine your grandma for a minute, and think of everything you associate with her. Here, “grandma” is a trigger for other thoughts, feelings, and maybe even physical sensations, just like an old song from our childhood can trigger a cascade of memories and associated feelings. In both cases, very different areas of the brain are activated to a lesser or greater extent. This would be a “grandma neuromatrix,” but your grandma matrix is guaranteed to be different from my grandma matrix. That’s also the case for the pain neuromatrix. Pain and anxiety are individual, and always real for the person experiencing them. Saying things like, “Don’t make a fuss,” or, “It’s not that bad,” don’t help anyone.

In my experience, it’s highly likely that much of your pain and anxiety will be alleviated if you develop your training with neuroathletic exercises and practice daily—because your brain gets better input from various systems in your body. Your “maps” become precise—and your brain can navigate more confidently and make better predictions about the future with better maps.

This excerpt about riding anxiety from Neuroathletics for Riders by Marc Nölke is reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books (www.HorseandRiderBooks.com). This is a web exclusive for Horse Illustrated magazine.